A Modest Year in Israel: When Young Women go to “Seminary”

Eighteen year-old girls in New York, London and Paris are packing their suitcases. Slightly worried that their suitcases are overweight, they are even more worried that they will return overweight from their year abroad in Israel, in a religious seminary, or midrasha, in Hebrew.

Across Israel (well, actually mainly across the affluent areas of Jerusalem) the doors of the academic Jewish year 5775 will open in the first week of September, 2014.

A well-groomed cohort of young women will immerse themselves in an intense year of advanced Jewish studies complemented by extensive touring and volunteer work. I’d argue that ‘sem’ as these places are affectionately referred to, is a microcosm of contemporary Orthodox life and are a powerful tool for the socialization of young women.

The competition to attract girls is fierce and for a seminary to succeed, it needs to have a strong brand, an effective marketing campaign and a strategic business plan. Parents who are paying an average of $20,000 USD for 10 months (this covers fees, accommodation and some food) need to be convinced that the seminary is going to cater to their daughter educational, social and emotional needs. Further, in Orthodox circles where gender relations are more circumscribed, some parents are often concerned that the choice of sem will influence the type of boy their daughters will be introduced to for potential marriage. Therefore, in loco parentis for the year, each seminary must establish its credibility to attract its clientele and online fora can be helpful.

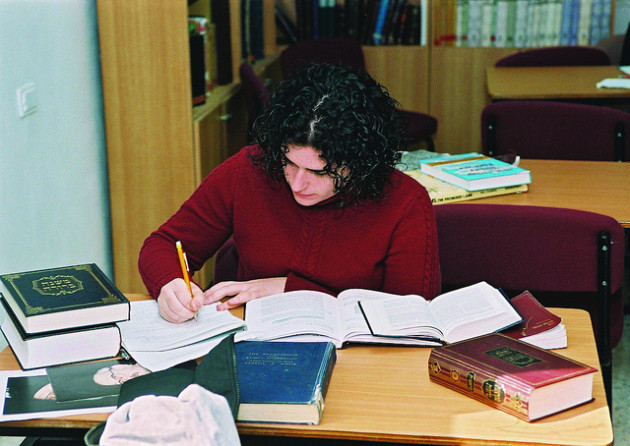

Recent allegations regarding improper behavior towards young women by Rabbi Aaron Ramati and Rabbi Elimelech Meisels highlights some of the difficulties parents face when choosing a seminary. Other than knowing students who went to a particular seminary, the first place to look is at their website. These sites consistently show groups of attractive, slim and smiling young women in certain poses – there’s the group hug on a tree top or during water sports, the girl poised with a pen over her notebook, girls helping in a range of charities and teachers with beatific grins. However, for a more pointed analysis, one must look to the curriculum.

As Torah and Talmud study is mandated for men, the male yeshivas have much less variety in the core curriculum, however, the seminaries are free to develop their own timetables as advanced Jewish women’s education for women is a relatively recent phenomena, largely in response to women’s advanced secular education. While all seminaries will structure their day around the study of Jewish texts, it is the selection of texts, the attitudes of the teachers and the approach to learning demonstrate the seminary’s Weltanschauung. The sem that is teaching Talmud will attract a different sort of young woman than a sem with a track record of girls getting married the year afterwards. A sem that engages these young women in rigorous Talmud study every morning, encouraging them to study ‘b’chevruta’ in pairs, has a very different view of women’s education and their role in the intellectual life of the community than a sem that shuns Talmud study and focuses more on Bible and personal development.

Further, a small number of sems offer an integrated study/volunteering option; for example, one is closely affiliated with a Jerusalem hospital and offers volunteering opportunities within the hospital, another offers arts and music activities to complement their Torah studies while another is based in a foster home for disadvantaged Israeli children and the girls study and also help care for the children. Rather than look at these seminaries as ‘soft options,’ it’s wonderful that there are a range of opportunities to suit areas of interest and skills – it’s a much healthier approach than the male yeshivot which are generally much narrower in their selection of texts and opportunities for extra-curricular activity.

Despite these variations, one thing is constant: notions of modesty permeate the sem experience, and with rare exception, girls are expected to wear knee-length skirts and loose-fitting tops. There are nuances to this code: in some places, sleeves must cover the elbow, while in others, the sleeves may fall shy of the elbow by a couple of inches. Some places require stockings be worn summer and winter while others allow bare legs but demand covered toes. A small number are more flexible when it comes to hikes, allowing the girls to wear loose baggy trousers to preserve their modesty. Peer pressure and social norms ensure that inappropriate text on T-shirts, excessive jewelry or outlandish hairstyles are discouraged.

This year of intense 24/7 communal living, away from one’s family, heightened by charismatic teachers and influenced by the seminary’s ideology, is also a harbinger of a life to come. A seminary offering opportunities for women to become religious leaders and arbiters of certain aspects of religious law is very different to a seminary focused on encouraging women to be dedicated homemakers supporting their future husbands who will continue to learn in a kollel, supported by their parents or charitable donations. Unfortunately, religious society is structured so that these two approaches are essentially mutually exclusive. A year in seminary is an expensive gamble and parents need to ensure that their eyes, as well as their wallets, are open before they send their daughter away.

Orthodox educator Rabbi Elimelech Meisels sued for sexual assault

Read more: http://www.jta.org/2014/08/08/news-opinion/united-states/orthodox-educator-rabbi-elimelech-meisels-sued-for-sexual-assault#ixzz3CI5pXd8s

Read more: http://www.jta.org/2014/08/08/news-opinion/united-states/orthodox-educator-rabbi-elimelech-meisels-sued-for-sexual-assault#ixzz3CI5pXd8s