What the SAR sex abuse report didn’t say

Stanley Rosenfeld was a pedophile. He was also inspirational, and that's no minor detail, it's a key lesson for today

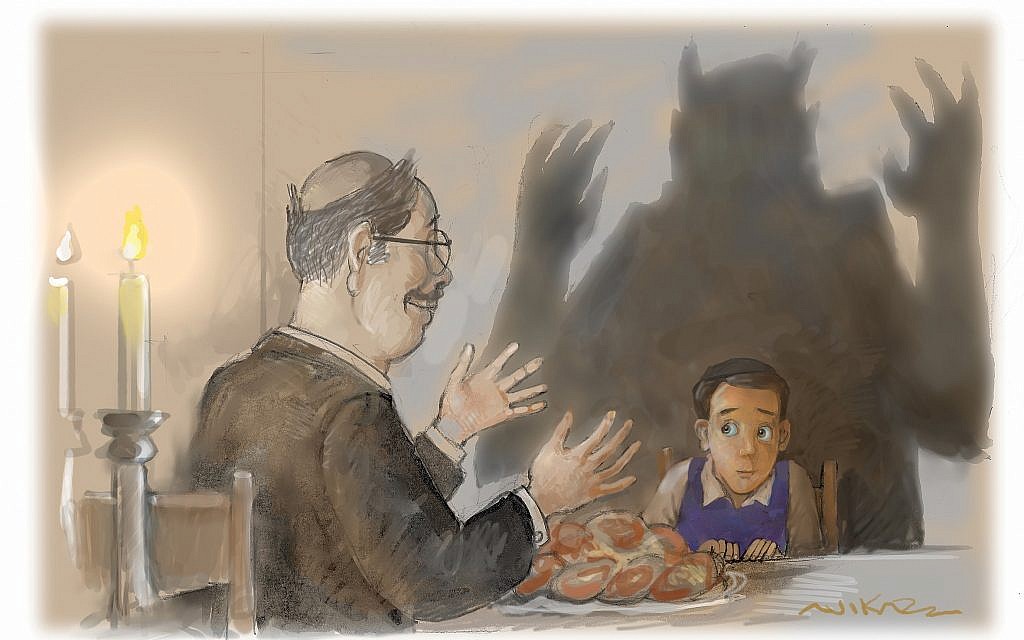

It was the first time I ever experienced a full, orthodox Shabbat experience. I remember the savory chicken fricassee that Rosenfeld prepared for the four of us for Friday night dinner. I remember singing zemirot at the Shabbat table for the first time, especially the spirited tune for zur mi-shelo.

Rosenfeld had a terrific tenor voice, and served as a cantor. I remember playing scrabble Shabbat afternoon and how taken I was that you could keep score by using a fat dictionary, and inserting a page-marker as the score progressed. I also remember the pillow fights and play wrestling that went on, which included Rosenfeld grabbing me in an area of the thigh that seemed a bit too high up. But I thought nothing of it at the time. All in all I had a beautiful Shabbat experience, and would tell many people thereafter that it was a catalyst toward my taking on Shabbat observance.

You can find reference to the pillow fights and thigh-grabbing on p. 10 of the T&M report, but no mention of any of these other details. Why are they important? Why remotely suggest anything positive about a monster?

If we are to prevent these events from recurring, we need to understand how they were allowed to happen in the first place. The literature of sexual abuse teaches us that predators go to great lengths to groom victims and that one of the central pillars of this activity is to engage in activity that builds trust and reverence in the eyes of the community. The moral of Little Red Riding Hood is not to trust strangers. The moral of Rosenfeld’s shabbat invites is how to not to fall victim to precisely those in whom we trust. Could it be that my Shabbat was a “decoy” designed to lull the school and community into a sense of trust, so that on another Shabbat he could attack his favored prey?

The school’s mandate to T&M was to investigate allegations of misconduct and to determine whether anyone within the SAR community had knowledge of such misconduct. Thus formulated, the mandate focused on past guilt. The picture it paints of Rosenfeld is that of the monster that he truly is.

But Rosenfeld was not perceived by the community as such, and the next predator in our midst is likely also someone of good standing, who also seeks to groom his victims by engaging in exemplary behavior. Had the report sought to understand the totality of Rosenfeld’s behavior, readers of the report could have developed a more refined sense of how such predators work, and sharpen awareness for the future.

The SAR report follows on the heels of a similar report from the Ramaz School just a few weeks earlier. Taken together, the two reports reveal a remarkable phenomenon: the circle of people who knew or had heard of sexual abuse was incredibly wide. In both schools it included administrators, teachers, parents, and students. And yet in neither school (nor in similar episodes elsewhere in the orthodox community) did anyone report the allegations of misconduct to law enforcement, nor to the press, nor to the wider Jewish community alerting to the presence of predators in our midst.

These reports copiously document what seem in hindsight a series of missed signals and opportunities to prevent further damage. How could all of these people – administrators, teachers, parents and even students once they got older – have failed to act to protect others? It is so easy to stand in self-righteous judgment of an entire generation of our community – but foolhardy to do so.

How apt that this question of judgment comes to the fore of our community, in this week that we read Rashi’s famous comment at the beginning of the story of Noah and the flood. Noah, the Torah says, was “a righteous man in his generation.” Rashi brings two interpretations that correspond to two views of moral agency. One view says that at all times all individuals have the same moral faculties and the same potential for moral greatness. By this view, had Noah lived in the generation of the great Abraham, his own “righteousness” would have appeared entirely unremarkable. But another view says that had Noah lived in the time of Abraham, surrounded by people of that stature, he would have been ever more righteous. By this view, we live in splendid delusion when we think we are really thinking and acting as free, autonomous individuals. Rather, all of our habits and attitudes are socially influenced. The generation makes the man.

And, likewise, the generation makes the administrator, the teacher, the parent and the student. Were all of those who failed to act in the 1970’s to face those same issues today, I suspect they would act differently. And conversely, let us not fool ourselves; had we been the ones to face these issues forty years ago, we likely would have taken – or failed to have taken – the same steps they did. There is no exoneration here. Those that knew had a responsibility to act. But let us learn from those mistakes in humility rather than in self-righteousness. Perhaps most of all let us try to understand how an entire generation got this wrong. If we do that, then maybe – just maybe – we will be able to train a critical eye on our own behavior, so that a generation from now, no one asks us how we got it all wrong ourselves.

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/what-the-sar-sex-abuse-report-didnt-say/?utm_source=The+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=daily-edition-2018-10-10&utm_medium=email