Records

from 18th century Prague show that the opening of Jewish coffee houses

on Shabbat enjoyed the approval of the city’s rabbinic leadership.

In the middle of the

eighteenth century, religious life in the Jewish community of Prague was

at its high point, with nine well-known synagogues and dozens of study

houses. But at the same time that the learned men of Prague were

producing vast Torah scholarship and the yeshivas were bustling with

students, another institution was gaining popularity – the coffee house.

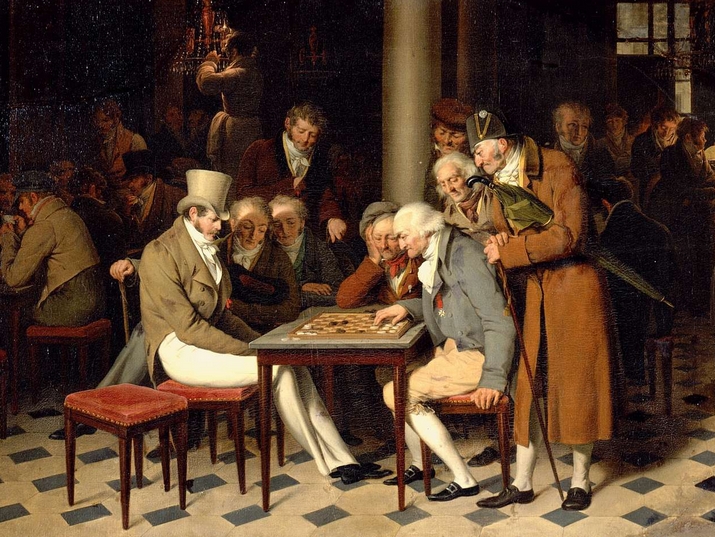

Coffee houses became popular soon after coffee’s arrival in Western

Europe, and often offered more than just a drink; they were a place to

spend leisure time playing games and discussing current events with

friends and strangers. Rabbinic sermons and writings from this period

warn of the spiritual threat posed by the coffee house. These

establishments’ diverse environment and leisure culture competed with

the traditional Jewish lifestyle of worship and study.

In spite of this potential culture clash, the records from that time period in the Pinkas Beit Din

– the minute book of the rabbinic court of Prague – show that the

opening of Jewish coffee houses on weekdays and, shockingly to modern

ears, even on Shabbat, enjoyed the approval of the city’s rabbinic

leadership, along with careful, detailed rabbinic-halachic regulation.

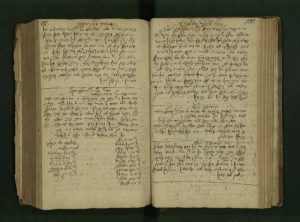

The Pinkas (minute book) of the Rabbinic Court of the Holy Congregation of Prague, currently

preserved in the Jewish Museum of Prague, is a hand written book which,

records the decisions of the rabbinic court, one of the most important

governing bodies of the Prague Jewish community. This pinkas,

written in a mix of Hebrew and Yiddish, begins in 1755 and survived the

Holocaust even as the community it records was wiped out, provides

important testimony to Jewish daily life in Europe.

In the Prague Pinkas Beit Din,

the numbers alone – seven discussions about coffee houses within

fifteen years – tell us how pressing and how complex this issue was. The

entries show a swift progression, from disapproval and severe

limitations to support with minimal caveats. Evidently community members

had embraced coffee-house culture and were not about to give it up. The

pinkas entries also show the style of religious leadership adopted by

the rabbinic courts of Prague in this case: instead of opposing a

cultural trend that threatened traditional life, the rabbis accepted the

new trend, which gave them the opportunity to regulate and contain its

impact, and to integrate the new institution into the traditional mode

of Jewish life.

One of the first discussions in the pinkas,

from around 1757, begins by taking a hard line – Ideally the coffee

houses in the Jewish ghetto should be closed, and people should instead

dedicate their time to Torah study. Since that is impossible, they

should open only for an hour in the morning, after morning services at

synagogue, and then for an hour following afternoon services. Women

should never enter coffee houses. With regard to Shabbat, “no man should dare to go to the coffee house and drink coffee there on the holy Sabbath. This is punishable with a large fine!”

This discussion is followed by another paragraph, presumably added days or weeks later:

However, due to the travails of war (presumably the siege of Prague in the spring of 1757, part of the Seven Years War)

and other concerns, many have protested that we cannot be so stringent

on this matter… the way to distance from sin will be that on the holy

Sabbath, no one should go to the coffee houses to drink coffee, but

anyone who wishes to drink should bring it to his home. And on weekdays,

any time they are praying in the Old New Synagogue (Altneuschul), no

man should dare go drink in the coffee house.

The added paragraph shifts the balance significantly, permitting Jews to frequent coffee houses at all times except

during prayers; allowances are made for procuring coffee on Shabbat as

well. Apparently the Jewish coffee sellers had an arrangement in which

customers paid before or after Shabbat, and they could prepare the

coffee without violating Shabbat laws about cooking, perhaps with the

help of non-Jewish workers. The main concern is the propriety of

spending time in the coffee house on Shabbat, so getting the coffee as

takeout is a suitable compromise, but not one that lasted long.

The next two entries on this topic in the pinkas,

dated 1758 and 1761, are each signed by eight Jewish coffee house

owners. One declares that coffee will be sold only until noon on

Shabbat, and one states that coffee will be sold without milk on

Shabbat, presumably in order to avoid serving dairy to customers who had

just eaten a meat meal.

A fourth entry, dated 1764, declares:

From this day

onwards, on Shabbat and holidays, women are not to enter coffee houses

to drink coffee at all. And even on weekdays, from 6 PM onwards, no

woman or women should be found in the coffee house…

These entries assume

that, despite earlier restrictions, women are indeed entering coffee

houses. Moreover, coffee houses are not only providing coffee for

takeout on Shabbat, customers are sitting and drinking coffee there, and

the rabbinic court is only trying to limit that clientele to men.

A fifth entry, dates 1774, states:

The owners of the

coffee houses stood before the rabbi and the rabbinic court, who warned

them that they should be careful to avoid selling coffee on Shabbat and

holidays to non-Jews, as the prohibition of commerce on the Sabbath

applies. They are permitted to sell only to Jews, for the sake of Oneg

Shabbat, delighting in the Sabbath day, since not everyone is able to

prepare coffee for himself on Shabbat at home.

To the rabbis of

eighteenth century Prague, the coffee house’s ambiance of levity and

cultural exchange competed with the traditional understanding of the

proper Shabbat atmosphere. The rabbinic court therefore made efforts to

restrict Jewish coffee houses’ activity on Shabbat, with limited

success. But in their final entry on this topic, the Prague Beit Din

provided the coffee houses with a religious stamp of approval, pointing

out that Jews attending coffee houses on Shabbat was in fact a

fulfillment of the religious injunction to delight in the Sabbath day.

The rising cultural significance of coffee in European regions, since

its import a few decades ago, is now reflected in the the pinkas; the

new product is incorporated into halachic language, labeled, for the

first time, as “Oneg Shabbat” – a positive value which should be

carefully considered. The coffee house and the synagogue need not

always be rivals: within certain parameters, both could be part of a

meaningful and enjoyable Sabbath day in Prague.

The National Library

of Israel, together with the Central Archives for the History of the

Jewish People in Jerusalem, holds the largest collection of pinkasim in

the world. Through international academic co-operation, the Pinkasim Collection

aims at locating, cataloguing, and digitizing all surviving record

books, making them freely available. At the first stage of the project,

the focus is on pinkasei kahal, the pinkasim of the central governing

body of Jewish communities. On June 20th, the National Library will host an event marking the launch of the Pinkasim Collection, which will feature experts from around the world, and will include a lecture by Maoz Kahana about coffee houses in Prague.