Expert in ancient DNA and wildlife forensics helps identify Oct. 7 massacre victims

Hebrew University Prof. Gila Kahila Bar-Gal uses her knowledge of difficult DNA extraction and physical anthropology as she volunteers at Abu Kabir

“I usually work also with DNA from archeological and museum samples. When you deal with ancient samples, the quality and quantity of DNA in the specimen is very low,” Bar-Gal said.

In the case of the October 7 victims, the age of the bones is not the challenge. Rather, it’s the fact that the terrorists set homes and bodies on fire, resulting in burned remains.

“The remains of the victims varied, including burned samples. The problem is the lack of presence of DNA in samples that were exposed to high temperatures like that,” Bar-Gal explained.

Before volunteering at Abu Kabir, Bar-Gal reached out to the Division of Identification and Forensic Science of the Israel Police, and the IDF.

“I called both the police and the IDF the night of October 7. I had collaborated with or done pro bono work for them before and offered to help,” Bar-Gal said.

“They said they didn’t need me at that point, so I thought of Dr. Bublil, whom I had met before, and called her. She told me my assistance would be very welcome,” she said.

Bar-Gal’s skill at extracting and amplifying DNA to arrive at a profile for comparison for police and other databases adds value to the efforts at Abu Kabir. Her experience in forensics and preparing evidence for use in court are also critical to arriving at identifications that everyone can rely on as 100 percent accurate.

She also brings to the table her knowledge from her position as director of the National Natural History Collections at Hebrew University, along with her background in physical anthropology and ability to morphologically identify human and non-human bones.

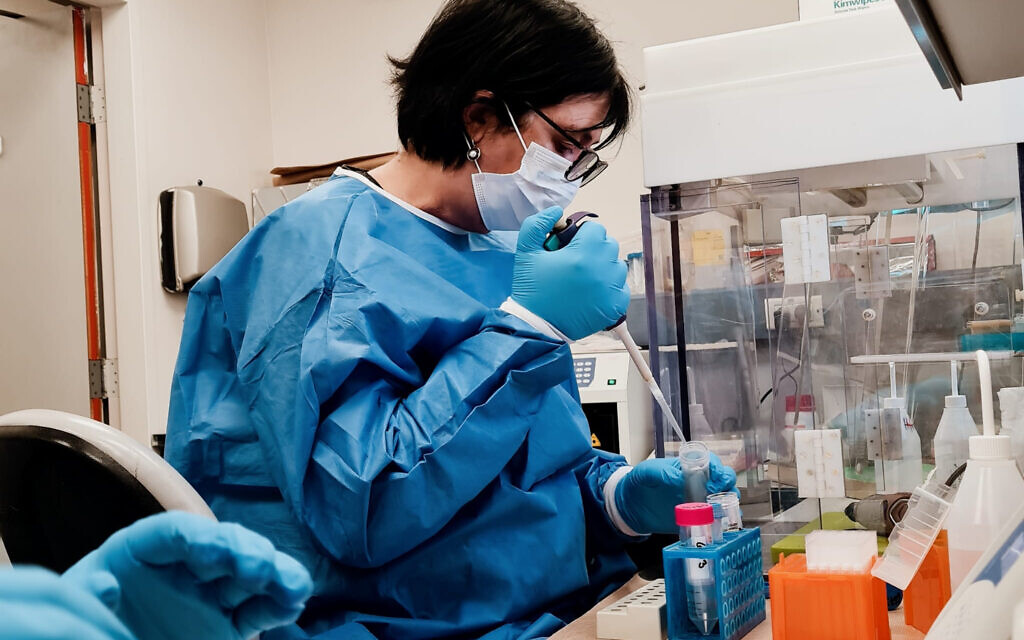

Bar-Gal does most of her work in Abu Kabir’s molecular forensic lab, but it is not unusual for her to be called to the dissection room.

“I consult with the doctors and anthropologists there about which bone — and which part of it — would be best for sampling for DNA analysis,” she said.

When bags of bones come in, the physical anthropologists lay the bones and shards out to try to piece together partial or whole skeletons. Bar-Gal sometimes helps them with their work to maximize the chances that DNA is extracted from bones from different individuals.

“The goal is to find the minimum number of individuals from a bag of remains brought in. If you have full bones or the indicative parts of bones, it is somewhat easier. But if you have small pieces of bones, sometimes it’s very difficult,” Bar-Gal said.

Bar-Gal shared that the only way for her to get through this experience at Abu Kabir is to look at the remains only as specimens. To do anything else would make it impossible to do the work. She finds this especially so when dealing with bones that she knows to have belonged to juveniles.

As hard as she tries to maintain an emotional distance, she was once a member of one of the attacked kibbutzim and knows people from others. Her personal background has provided challenging moments.

“The first week I got remains to sample, they were labeled with names and locations. It was very difficult. Since then, I’m only getting bags with numbers, so I don’t know where they are from, which is better,” she said.

There are still at least 10 missing or unidentified individuals from the October 7 massacre, and families have expressed their anger at the lack of clarity about the fate of their loved ones. In some cases, families were told that their loved ones were held hostage in Gaza, only to learn that they were actually dead following the delayed retrieval of their remains from the field or identification in the lab — or both.

“Families have expressed their impatience since the very beginning, but what they need to understand is that this is not like CSI and other TV series where they work on a sample and get a DNA profile in 45 minutes. It takes much longer,” Bar-Gal said.

“Just the stage of extracting the DNA from the sample takes about 15 to 20 minutes. Then that has to be in some buffers for two days to extract the DNA before amplifying it to reach a profile. The whole process takes a minimum of three to four days,” she said.

The process can be frustrating for the scientists too, as sometimes it proves unsuccessful. Bar-Gal said there were instances where she had to extract samples from the same bone three or four times.

On some occasions, bones are tested and all turn out to have belonged to the same person despite best efforts by her and the physical anthropologists to prevent this from happening. Families must also face the fact that as time goes on, remains become more degraded and the identification process becomes harder, if not impossible.

“It could be that we will not be able to identify everyone, but we keep trying. We are not giving up on sampling and trying to reach answers,” Bar-Gal said.