“I’m Famished”: The Excuse Maimonides Gave His Translator

From the moment he became chief physician at the royal court of Egypt, Maimonides found that he had almost no time left for anything else, not even to meet with the translator of his most famous work.

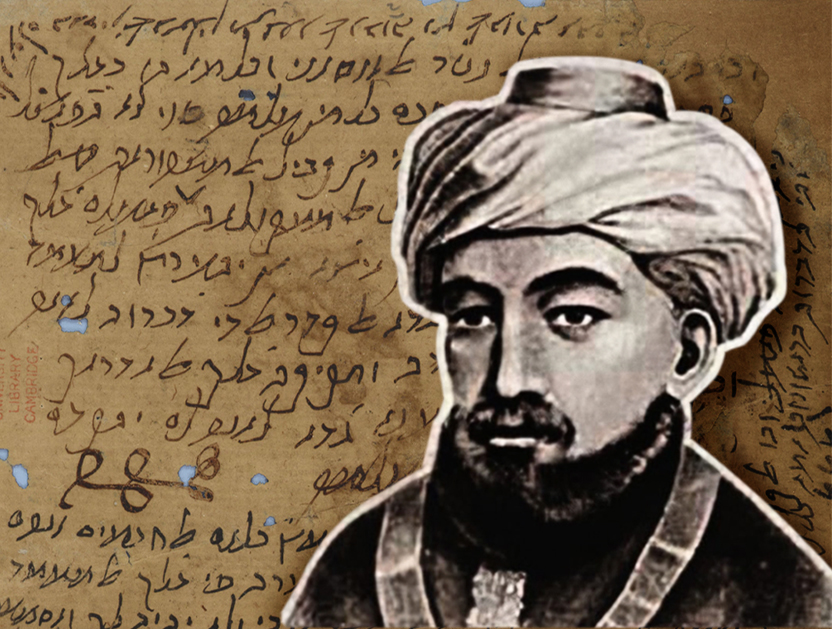

This story begins after the tragic death of the brother of Maimonides, Aaron, who drowned at sea during a trading voyage. In addition to the terrible personal loss, his death brought about a financial crisis for the family, whose wealth was tied-up in Aaron’s business ventures. Rabbi Moses ben Maimon – Maimonides – one of Judaism’s greatest legal authorities and its foremost philosopher, who would also serve as head of the Jewish community in Egypt and the surrounding regions, was forced to scramble to find a way to earn a living. Around the year 1178, he turned to medicine.

Thanks to his sharp intellect and growing reputation, it was only a few years before Maimonides was appointed personal physician to the royal court in Cairo. From that moment, the tone of his letters changed: urgency and exhaustion seeped into every written line. To his students and friends, he wrote of the immense demands on his time and energy, the constant stream of people who sought his help, and the strain of his new position.

Despite the ever-increasing pressures, Maimonides somehow managed to find time for extraordinary philosophical creativity and halakhic ingenuity. He wrote during the late-night hours, time meant for rest and renewal, and thus was able to complete The Guide for the Perplexed.

When he finished this great philosophical work, written in Arabic – the intellectual language of his surroundings – Jewish readers in Europe also longed to study it. The task of translation was taken up by Samuel ibn Tibbon, a member of a distinguished family of translators specializing in rendering Arabic works into Hebrew.

Working in France, the industrious translator sent Maimonides an unusual request. After reading The Guide in the original, he immediately recognized its immense importance, and the layers of concealment and complexity woven throughout. Even in his time, ibn Tibbon understood why readers sometimes called it “The Perplexing Guide.”

To clarify certain fundamental questions about Maimonides’ ideas and writing, ibn Tibbon offered to make the long journey from France to Egypt at his own expense, hoping to spend time in the philosopher’s company, however long Maimonides might allow.

Maimonides’ reply, however, was a firm refusal:

I live in Fustat, and the sultan resides in Cairo; these two places are two Sabbath limits distant from each other. My duties to the sultan are very heavy. I am obliged to visit him every day, early in the morning, and when he or any of his children or concubines are indisposed, I cannot leave Cairo but must stay during most of the day in the palace. It also frequently happens that one or two of the officers fall sick, and I must attend to their healing. Hence, as a rule, every day, early in the morning I go to Cairo and, even if nothing unusual happens there, I do not return to Fustat until the afternoon. Then I am famished but I find the antechambers filled with people, both Jews and Gentiles, nobles and common people, judges and policemen, friends and enemies — a mixed multitude who await the time of my return.

Maimonides then described how little time he had even to eat:

I dismount from my animal, wash my hands, go forth to my patients, and entreat them to bear with me while I partake of some light refreshment, the only meal I eat in 24 hours.

[Translation: Eliyahu Junik, via Sefaria]

Through this heartfelt description, Maimonides sought to dissuade his translator, and the many others who wished to visit him, from interrupting the few moments of rest he had left.

Before modern times, few rabbinic figures had left us such a clear window into their inner lives or such personal correspondence, especially remarkable given that Maimonides lived nearly a thousand years ago. The letters preserved in the Cairo Genizah offer a rare glimpse not only into the elevated thoughts of one of Judaism’s most brilliant philosophers and spiritual leaders – ideas often conceived in the quiet of the night and expressed (or concealed) in The Guide for the Perplexed – but also into the crushing weight of his daily responsibilities, and the relentless rhythm of a life divided between healing bodies and shaping minds.