Anger grows at Israel’s ultra-Orthodox virus scofflaws, threatening rupture with secular Jews

BNEI BRAK, Israel —The Shinfelds, an ultra-Orthodox Jewish

family in this most religious of cities, are used to being a bit at odds

with the rest of Israel. Their community's tradition of large families —

the couple has 10 children and 30 grandchildren — strict observance and

exemption from military service have long created friction with the

more secular majority.

But they say they have never felt hostility like they do now, as a

pandemic-exhausted nation has turned its rage at ultra-Orthodox

scofflaws.

As Israel endures its third national lockdown,

social media has been inflamed by images of black-clad men brazenly

crowding schools, weddings and other events, including 20,000 at a

recent Jerusalem funeral of a leading rabbi. Secular critics have cast

the ultra-Orthodox, fairly or not, as superspreaders supreme, a drag

chute on the country’s race to vaccinate its way out of the coronavirus’s grip.

“Now it’s not only tense — it feels like hatred,” said Vivian

Shinfeld, 60, of the anger she feels even from some less-religious

members of her own family. “Now it is starting to feel like a war.”

The Shinfelds consider themselves “modern” ultra-Orthodox. They

wear masks, have been vaccinated and condemned the covid-19 violators

who torched a bus a few blocks from their house

in protest of lockdown restrictions. But they too have become pariahs,

ghosted by old friends and unable to get a repairman to come fix their

refrigerator.

The backlash could have cultural and political impacts well after the pandemic ends.

“There has been a schism growing for a while, and the pandemic is

making it wider,” said Tamar El-Or, an anthropology professor at Hebrew

University and longtime scholar of ultra-Orthodox culture. “When this

virus is gone, nothing is going to be same.”

The ultra-Orthodox

— or Haredim as they are known in Hebrew — largely shun modern society.

For decades, Israeli governments have accorded them autonomy in

exchange for their leaders’ support in parliament and subsidized a

lifestyle that favors Torah study over employment with welfare payments.

“It’s time that we have one law, for everyone,” said Yair Lapid, a

leader of the parliamentary opposition, in a campaign ad contrasting a

classroom empty during the lockdown with another filled with

ultra-Orthodox students.

National elections are scheduled for March 23,

and opponents have seized on the anger as a cudgel against Prime

Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who is blamed for not enforcing

restrictions in a sector essential to his ruling coalition. (Just 2

percent of the fines issued last year for violating coronavirus

restrictions were in ultra-Orthodox areas, according to Be Free Israel, a

group advocating for religious pluralism.) Haredi parties, which often

serve as kingmakers in the parliament, hold 16 seats. Polls, including

one released in earlier this month by Channel 12 News, indicate 60

percent or more of all Israelis want ultra-Orthodox parties out of

government.

In January, Defense Minister Benny Gantz proposed ending the

ultra-Orthodox exemption from conscription, which is mandatory for other

Israeli Jews. Academics and business leaders are renewing their calls

for Haredi schools to teach basic math and science. Meantime, some

secular lawmakers continue to target the per-child welfare payments that

support large Haredi families.

Even within the community,

tensions are emerging between hard-liners and others who have begun to

seek education and careers outside their neighborhoods.

“You

can’t ignore it anymore,” said Hila Lefkowitz, an ultra-Orthodox

activist who is running for parliament as part of a new alternative

religious party. “The way that the Haredi society functions, with its

independence, now we are seeing the problems with that.”

The

contentious relationship between public health officials and the Haredim

goes back to the beginning of the pandemic. Most rabbinical leaders did

obey early orders to close schools and synagogues, but only

reluctantly, citing the central role of daily religious gatherings in

Haredi life.

As pandemic fatigue set in, defiance grew. Some

rabbis, complaining that secular Israelis were being allowed to gather

at mass political protests against Netanyahu each week, ordered the

religious schools, called yeshivas, to reopen. Weddings and funerals

continued, some of them drawing hundreds. Making up 12 percent of the

population, the ultra-Orthodox have accounted for more than a quarter of

positive coronavirus cases, according to Health Ministry data.

Two months into the vaccine campaign, Israel’s rate of new infections

has only just begun to bend downward. Its seven-day average of 6,952 of

new positive cases is down over three weeks from 8,624.

Government dictates, in any case, are anathema to the ultra-Orthodox,

many of whom reject state power in favor of biblical authority. As in

the United States, covid restrictions became political.

“If the government says, ‘Wear a mask,’ that’s a reason for them not to wear a mask,” said Itzhak Shinfeld.

Modern Haredim — who adhere to halacha,

or Jewish law, but don’t outright reject mainstream life — fear that

tensions between their community and wider Israeli society could rupture

the growing ties between these two worlds.

Almost two-thirds of ultra-Orthodox are under 19 and are entering

the workforce in greater numbers. According to Israel’s Central Bureau

of Statistics, more than 76 percent of Haredi women work outside the

home now, even as men still mostly chose a life of Torah scholarship.

The number of ultra-Orthodox students in higher education has more than

doubled in the past decade, although it remains below 13 percent.

Itzhak Shinfeld, who has recently been able to hire Haredi plumbers

and electricians, worries that this modest progress will be reversed if

secular politicians clamp down on the ultra-Orthodox in the name of

controlling the pandemic.

“We are in the middle of a big integration,” he said. “The minute they feel oppressed, they will close up the box again.”

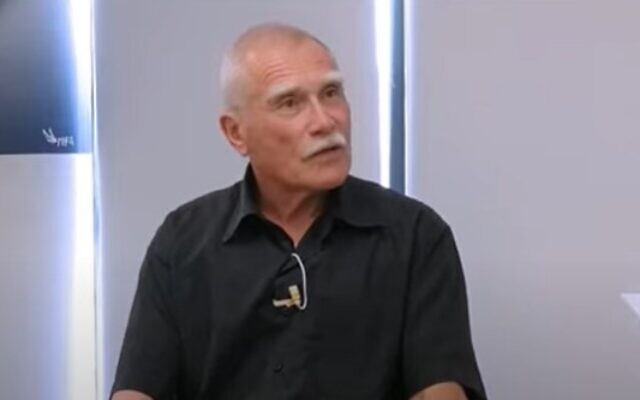

Shinfeld, 61, illustrates the divide within the Haredi world. He was

born and raised in Bnei Brak, one of the country’s centers of

ultra-Orthodox life, and educated at Israel’s largest yeshiva. He still

wears the traditional broad black hat and knee pants of the Gur sect

each Sabbath and has no television in his house.

But, after

studying the Torah for an hour every morning, he works as a lawyer and

owns a construction company. During a recent weekday visit on his patio,

he wore a blue dress shirt and black yarmulke. He served in the Army in

the 1980s, reaching the rank of captain, something unthinkable for

stricter Haredim. Lockdown tensions have only widened the gap between

security forces and the ultra-Orthodox, some of whom have taken to

pelting police patrols with rocks.

“Things that were normal then are not normal now,” he said, fingering his smartphone.

Some relatively moderate members of the community say they believe

their rabbis have failed them by openly defying government closure

orders, and this, in some instances, has called into question the

male-dominated hierarchy. Some Haredi women feel emboldened now in

asking for a greater say.

“There's no more trust between the

community and its leaders,” said Lefkowitz. “So there are people who

would never have entered political life now entering.”

The

Shinfelds hold their more conservative leaders accountable leaders for

flouting covid restrictions. But police, too, bear responsibility for

the worst clashes, they say, by storming into their streets in a way

that wouldn’t happen in a secular Tel Aviv neighborhood. Online scolds

have dubbed their community a “death cult,” but the couple share the

belief widely held among the ultra-Orthodox that they have been singled

out.

“I don’t want to see the synagogues open, but they should also close the protests,” Itzhak Shinfeld said.

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/anger-grows-at-israel-s-ultra-orthodox-virus-scofflaws-threatening-rupture-with-secular-jews/ar-BB1dwnRV?fbclid=IwAR1PiZ45ZbGxO2dSGjre6aEPGsZu3rorMWqVyedG9bsAx1LCGszeBAMIJKk&fullscreen=true#image=3

.jpg)