“For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens,” the Times article began (there were actually only two attacks). “Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom lights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he returned, sought her out and stabbed her again.”

|

Sophia Farrar Dies at 92; Belied Indifference to Kitty Genovese Attack

For

decades, the conventional narrative that defined urban anomie

overlooked a good Samaritan who heeded a dying woman’s cries for help.

The

story of Kitty Genovese, coupled with the number 38, became a parable

for urban indifference after Ms. Genovese was stalked, raped and stabbed

to death in her tranquil Queens neighborhood.

Two

weeks after the murder, The New York Times reported in a front-page

article that 37 apathetic neighbors who witnessed the murder failed to

call the police, and another called only after she was dead.

It

would take decades for a more complicated truth to unravel, including

the fact that one neighbor actually raced from her apartment to rescue

Ms. Genovese, knowing she was in distress but unaware whether her

assailant was still on the scene.

That

woman, Sophia Farrar, the unsung heroine who cradled the body of Ms.

Genovese and whispered “Help is on the way” as she lay bleeding, died on

Friday at her home in Manchester, N.J. She was 92.

Her son, Michael Farrar, said the cause was pneumonia.

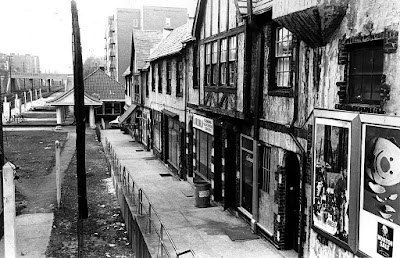

At around 3 a.m. on March 13, 1964,

the 28-year-old Ms. Genovese was stabbed repeatedly, raped and robbed

of $49 in two separate attacks by the same man as she returned home to

leafy Kew Gardens from her job as a bar manager.

The

murder was reported in a modest four-paragraph article in The Times.

Two weeks later, its interest piqued by a tip from the city’s police

commissioner, The Times produced a front-page account

of the killing that transformed the murder into a global allegory for

callous egocentrism in the urban jungle and undermined the

innocent-bystander alibi.

“For

more than half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens

watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew

Gardens,” the Times article began (there were actually only two

attacks). “Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their

bedroom lights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he

returned, sought her out and stabbed her again.”

That

account — epitomized by one neighbor’s stated excuse that “I didn’t

want to get involved” — galvanized outrage, became the accepted

narrative for decades and even spawned a subject of study in psychology:

how bystanders react to tragedy. Except that with the benefit of

hindsight, the number of eyewitnesses turned out to have been

exaggerated; none actually saw the attack completely; some who heard it

thought it was a drunken brawl or a lovers’ quarrel; and several people

said they did call the police.

And there was Mrs. Farrar.

According

to police accounts, trial testimony and interviews for “The Witness,” a

2016 documentary about the case, Mrs. Farrar, her husband and her son

were awakened by, in Michael Farrar's words, “a loud, bloodcurdling

scream.”

“The whole neighborhood had to hear it,” he said. The Farrars looked out the window, saw nothing, and went back to sleep.

Mrs.

Farrar said a frantic neighbor called her after 3 a.m. and reported

that Ms. Genovese was in distress in a vestibule in the back of the

two-story building where she and her partner, Mary Ann Zielonko, lived

on the second floor, across the hall from the Farrars.

Without

hesitating, Mrs. Farrar dressed, raced through a circuitous alleyway

and reached the vestibule just moments after the killer had left.

The

door was jammed; Ms. Genovese’s body was wedged against it from the

inside. Mrs. Farrar finally opened the door and found Ms. Genovese in a

pool of blood, moaning and gurgling and barely conscious, Mr. Farrar

says in the film. Mrs. Farrar cradled her, offered words of comfort,

promised that help was on the way and yelled for another neighbor to

call the police.

It was too late. Ms. Genovese died in the ambulance before reaching the hospital.

“I only hope that she knew it was me, that she wasn’t alone,” Mrs. Farrar says in “The Witness.”

That film, produced

and directed by James Solomon, traces an investigation by Ms.

Genovese’s younger brother, Bill, into the murder and the mind of Winston Moseley, the psychopathic killer who stalked his victim and died in prison in 2016 while serving a life term.

After the murder, Bill Genovese volunteered for the Marines and served in Vietnam, where he lost both his legs.

“It

would have made such a difference to my family knowing that Kitty died

in the arms of a friend,” Mr. Genovese, who was also the film’s

executive producer, says in “The Witness.”

Mr.

Solomon said in an email: “Sophia Farrar’s heroic actions complicate an

overly simplified parable of urban apathy. Her story does not fit

neatly with the notion that no one helped.”

Ms.

Genovese and Mrs. Farrar were not anonymous neighbors. Ms. Genovese

sometimes drove young Michael Farrar to school in her red Fiat. Mrs.

Farrar would occasionally care for Ms. Genovese’s poodle.

“It’s

clear she went to great efforts to save and comfort Kitty, giving the

lie to the idea that no one helped and no one cared,” Jim Rasenberger,

an author who reviewed the case 40 years later in The Times, said by email. “There ought to be a statue to her in Kew Gardens.”

Sophia

Veronica Laskowski was born on Jan. 11, 1928, in Brooklyn, one of 10

children of Polish immigrants: Victoria (Bartold) Laskowski and Edmund

Laskowski, a truck driver.

After

graduating from Queens Vocational High School, she worked for the Army

Signal Corps and Western Union during World War II. She later managed a

doctor’s office and performed secretarial and communications work for

the American Cancer Society.

In 1949

she married Joseph Farrar, a sheet metal worker for the Long Island Rail

Road. The couple remained in Kew Gardens for about six years, then

moved to the Richmond Hills section of Queens.

In

addition to her son, Mrs. Farrar is survived by her husband; their

daughter, Deborah; four grandchildren; a great-grandson; and a brother,

Richard Laskowski.

In several retrospectives decades

after the murder, The Times reassessed the original account, concluding

that more neighbors might have heard Ms. Genovese’s screams than

actually witnessed the attack. But only one

Times article, during Mr. Moseley’s trial, even mentioned Mrs. Farrar’s

name, reporting that she and Ms. Zielonko found the victim in the

vestibule.

Since Mrs. Farrar was

interviewed on camera in “The Witness,” though, among those who

criticized The Times’s failure to report her presence in earlier

accounts of the crime was Joseph Lelyveld, who was the executive editor

of The Times in the 1990s. He has called the omission “inexcusable.”

Charles

E. Skoller, the prosecutor who handled the case, described her role in

his book “Twisted Confessions: The True Story Behind the Kitty Genovese

and Barbara Kralik Murder Trials” (2008).

Mrs.

Farrar, “a petite woman in her early 30s with a young baby at home,

fell to her knees and cradled Kitty in her arms,” he wrote. “The police

documents confirmed that Sophie was the only person to show concern or

compassion for Kitty Genovese during the early morning hours of March

13, 1964.”