What Happened in Lakewood

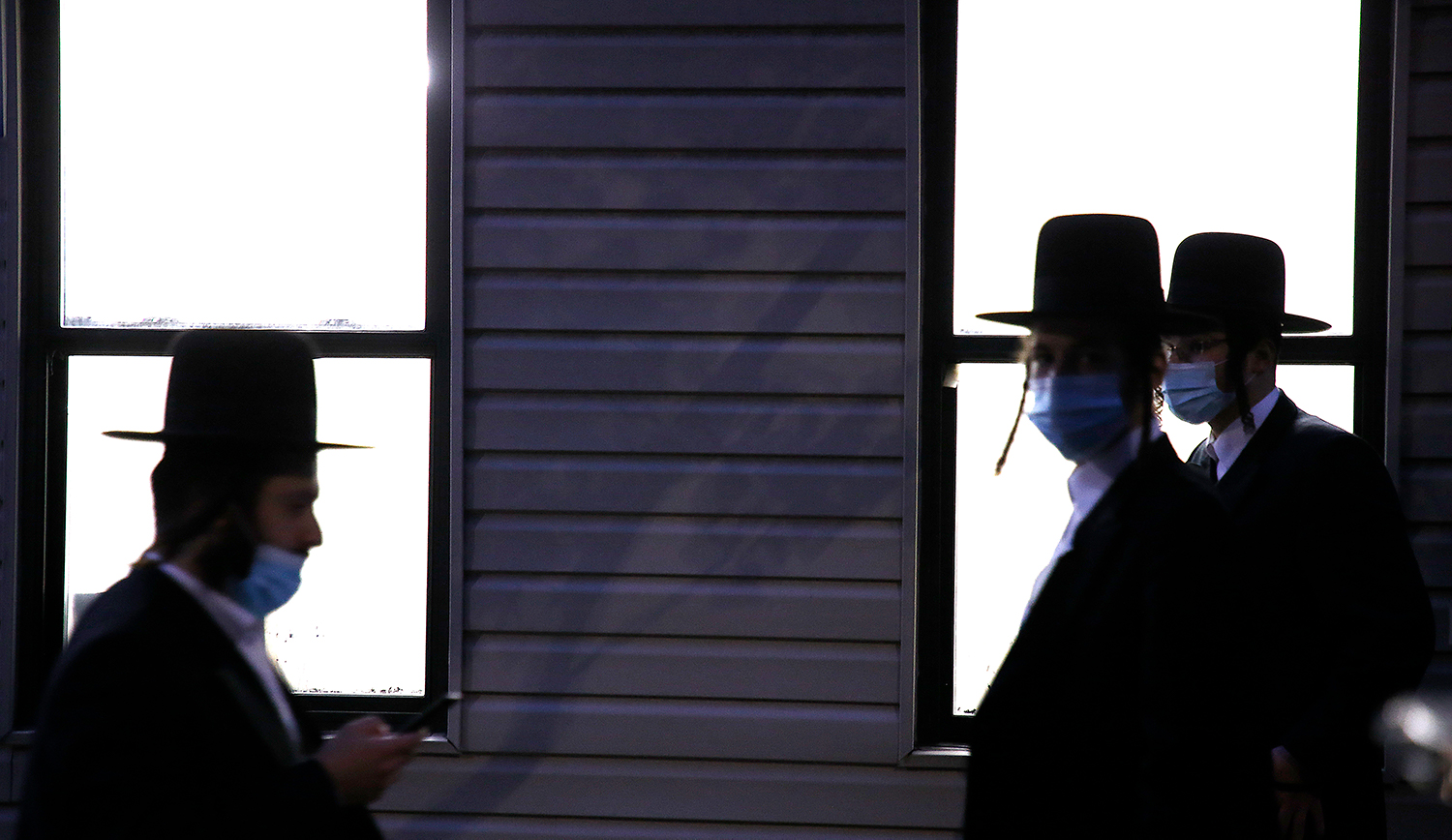

Why American Ḥaredim have responded so differently from other Jews to the pandemic.

“It is not difficult to build a sanctuary,” wrote the great 19th-century German rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch. “It requires a moment of inspiration and a mood of generosity. But it is much more difficult to generate an enduring enthusiasm to be retained for years—or even a lifetime. Without such support, the structure itself would remain cold and lifeless. Enthusiasm for the Sanctuary must never subside. The Sanctuary and its goals must never be considered out of date.”

Hirsch, the pioneer of synthesizing modern secular culture with Orthodox Judaism, was writing about the annual half-shekel donation for the upkeep of the Jerusalem Temple, deriving from this commandment—observed only symbolically in the Temple’s absence—a vital lesson about the role of the synagogue.

In writing the story of how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed Jewish communal life in in the U.S., Jack Wertheimer acknowledges that in his research he did not attend to the dramatically different effects it had on American Ḥaredim. But an examination of the latter can be instructive in making sense of the broader situation of American Jewry. In providing such an examination, based on my own experiences, I also hope to correct misconceptions about ḥaredi life during the pandemic, and to explain why Ḥaredim insisted on keeping their houses of worship open while others were closed. But first it’s necessary to say something about the ḥaredi conception of the synagogue, which is different from that of other American Jews.

The word synagogue derives from the Greek, which is, as Wertheimer notes, a direct translation of the Hebrew beyt knesset, meaning “house of assembly.” These terms describe how most Jews see its purpose: as a place of gathering. Over the years, ancillary functions have been added to its core use as a place of prayer, which has become a major part of what synagogues do. In this way, the synagogue has become a place of gathering at least as much for its own sake as it is a place to gather for worship. The closures of synagogues, or their replacement with virtual simulacra, thus becomes a social issue as much as a religious one.

Interestingly enough, Ḥaredim do not refer to a house of worship as a synagogue or beyt knesset. Instead they call it either a beyt midrash—a house of study—or a shul—the Yiddish term that derives from the German word for school. As it is outside of ḥaredi communities, prayer is the building’s primary function, but unlike other American synagogues, its secondary use is not for social life, but for study.

That this is so is due to the distinctive ḥaredi understanding of religious obligation as well as the structure of American ḥaredi society. Ḥaredim believe that the continual lifelong pursuit of the study of Torah—considered, like prayer, a form of service to God—defines these buildings and congregations. In ḥaredi shuls, only worship and study are acceptable activities. The Shulḥan Arukh, the standard code of Jewish law, contains an entire section dedicated to regulations about what is and is not permitted in the synagogue. While it is typical for other denominations’ synagogues to use their main sanctuary for affairs of a secular nature, such as hosting political or educational figures or community events, this is much less common among Ḥaredim. And while ḥaredi shuls often provide social services, such as meals for the needy, these activities are just as often left to other communal organizations.

Indeed, the ubiquitous presence of such organizations speaks to the close-knit nature of ḥaredi society, which allows shuls to have a more focused purpose. Because ḥaredi life is so deeply communal, there are charities, neighborhood-watch groups, schools, and a great many other institutions that serve purposes that in other communities are assigned to the synagogue. Similarly, Ḥaredim don’t need the synagogue to create opportunities to socialize with other Jewish families. They tend to live in their own neighborhoods, frequently attend weddings and engagement parties, and have constant opportunities for social interaction with coreligionists. Thus the purpose of the ḥaredi shul is not to create a community; it instead emerges as a place of study and prayer within a preexisting, fully alive Jewish community. Yet even as the function of the ḥaredi shul is narrower, its presence in the life of a typical ḥaredi male, who attends shul at least three times each day, and sometimes more, is greater.

Film screenings, cooking and yoga classes, and programs “to discuss questions of racial justice, equity, and the preservation of democratic norms” might find a place in a synagogue, but they are anathema to a ḥaredi shul. If a ḥaredi Jew attends a cooking class, or a yoga class, it would likely be with other Ḥaredim, just not in a synagogue. And although members often pay dues, the ability to collect dues factors into considerations in a very minimal way. Precisely because shul attendance is seen as a fundamental need, those with means often see the support of their shuls as a necessary investment, and their voluntary contributions go far to cover expenses.

For many synagogues, the migration out of physical buildings and into a virtual world driven by the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted just how unnecessary the physical facilities are. If synagogues are merely social centers or locations for the Jewish aspects of life, why not replace them with online spaces? If anything, experiencing Jewish religious behavior in the home might lead to a firmer Jewish identity for those who would otherwise only engage in a synagogue, as some of Wertheimer’s interlocutors indeed suggested.

Suppose there is another pandemic, with a virus even more contagious that COVID-19, that requires a truly drastic response. Would we be able to get the needed buy-in from the ḥaredi community, which has rediscovered its deep need for its shuls when they were shuttered, while becoming far more skeptical of expert advice? That’s what keeps me up at night.