Thursday, May 08, 2025

One who studies Torah without national responsibility, one who learns without combining study with acts of kindness, one who walls himself inside the four cubits of the beit midrash and does not hear the needs of the Jewish People—his Torah is deficient. A moral obligation lies on every person, and certainly every Torah scholar, to shoulder responsibility for society. Since in the State of Israel the existential and security threat stands at the forefront of our national challenges, yeshiva students must take part in addressing it.....

The Complexity of Hesder Revisited

| |||||

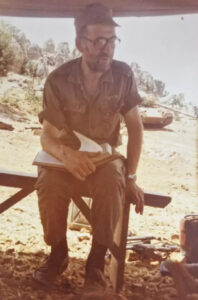

| R. Aharon Lichtenstein, in uniform, delivering a shiur to Hesderniks in Lebanon, Summer 1982 | |

In the ten years since the passing of my father, my teacher and master, Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l, we have faced difficult and challenging times, foremost among them the massacre on Simchat Torah 2023 and the ensuing war. My father, now gone for a decade and receding into the mist of the past, has not experienced these ordeals together with us. Yet, although his voice has been silenced, the influence of his consistent Torah-based ethical values has not ceased.

I wish to present here a small selection of his vast worldview related to an urgent issue in Israel’s public discourse—his clear position obligating all yeshiva students to enlist in the Israel Defense Forces and share the burden of combat. I will first present his position on the damage done to Torah by those who remain exclusively in the beit midrash at such an hour, and then propose a course of action, based on his teachings, for expanding the circle of yeshiva students enlisting. All this is offered with the hope that his words, spoken from a pure heart, will enter the hearts of my readers.

In 1981, in the pages of TRADITION (19:3), my father published his essay “The Ideology of Hesder” (published the following year in Hebrew in Yeshivat Har Etzion’s journal, Alon Shevut #100). True to form, he addressed the topic from multiple angles. He presented military service as an urgent necessity, as a clear and present mitzvah; laid out the justification for shortened military service for yeshiva students; extolled the contribution of Hesder’s combination of study and service to the nation and the IDF; pointed out the difficulties inherent in the Hesder track; and offered solutions.

His primary halakhic argument presented Hesder as a clear fulfillment of “Torah combined with acts of lovingkindness.” As one who consistently followed the ways of Beit Hillel, giving precedence to his opponents’ arguments before his own, he fairly and thoroughly presented the views of those who exempt yeshiva students from military service. He engaged with their arguments and sources, but ultimately concluded that they do not provide a sufficient basis for a sweeping and definitive exemption for Torah scholars.

The essay was published over forty years ago, closer in time to the founding of the Hesder movement in 1953 than it is to our own day. It expresses an original position that at that time was not accepted even among other heads of Hesder yeshivot. Anyone reading the essay feels its polemical tone—one that, as often happens, engages most ardently with those closest to one’s own position. My father chiefly confronted the track known as “Hesder Merkaz” (centered on Yeshivat Merkaz HaRav). He argued that the key difference between the varieties of Hesder experience was whether they viewed military service merely as a necessary preparation for war, should it arise (as all in Israel reasonably suspected it would; indeed, the First Lebanon War broke out less than a year after the essay was published), or whether they also saw bearing the burden of ongoing national security as an inherent obligation for Torah scholars.

Here, I will highlight a paradox in the positions of both sides. Merkaz HaRav, which champions Rav Kook’s Torah—a Zionism of action that sees the State of Israel as the realization of prophetic vision—nevertheless supports shorter military service for yeshiva students in favor of increased time on the benches of the beit midrash. Meanwhile, my father, whose Zionism drew from entirely different sources, called for longer military service for students of Torah. This paradoxical reversal is rooted in a deep difference in worldview regarding the sacred, the secular, and the nature of the State of Israel. With the “image of father appearing before us in the window” (cf. Sota 36b), I will attempt to offer an explanation and reexamination of the issue through the lens of our present experience of a year and a half of continuous warfare.

Hesder as an Ideal

When my father arrived in Israel in the summer of 1971 there were few Hesder yeshivot. Many of the roshei yeshiva and ramim of that time had grown up in the Haredi system. How did they view their Hesder students? I heard from Rabbi Haim Sabato that his teacher at Yeshivat HaKotel, Rabbi Yeshayahu Hadari zt”l, described Hesder’s goal as “to bring Torah to the boys of Bnei Akiva.” The assumption behind that statement was that Hesder represents a compromise or concession—a yeshiva for Religious Zionists (who probably couldn’t handle a “real” yeshiva), where they could learn a bit of Torah alongside serving in the army.

Such a yeshiva was seen as a realization of the Mizrachi movement’s vision, emphasizing “Torah and…” In other words, much of the Hesder leadership viewed its very own institutions as a bedi’avad (less than ideal) option, meant for those who had already chosen the path of Religious Zionism and its compromises. For a boy whose soul thirsted for Torah and who aspired to grow in learning their recommendation was to study full-time in a “proper” yeshiva, nicknamed the “Holy Yeshivot,” and take the exemption from army service.

My father represented a completely different orientation: Hesder as an ideal (lekhathila). Rabbi Re’em HaCohen told me that as he was finishing Netiv Meir high school and was deliberating about his next step, he consulted with my father. He asked him about the choice between a “Holy” and a Hesder yeshiva. Father surprised him with his answer: He said that someone unable to handle the dual challenge of serious Torah study along with the military should opt for a yeshiva without army service. But one who is strong and capable of both deep Torah study and army service should choose Hesder—which he saw as the more challenging but preferred path.

Indeed, anyone who learned at Yeshivat Har Etzion knows that my father viewed the yeshiva as a kind of Volozhin-like ideal in terms of his expectations of us, his students. Those expectations were high—in terms of diligence, academic level, and aspirations. He envisioned a yeshiva where the sound of Torah would not cease for even a moment. True, there were extended periods when students would leave the beit midrash, but this did not diminish the vision that here, the banner of Torah would be borne high—equal to or surpassing other yeshivot.

This worldview is expressed in the main argument presented in “The Ideology of Hesder,” regarding Torah combined with hesed (acts of kindness). My teacher and master, Rabbi Yehuda Amital zt”l, shared this worldview, and that is why he drafted my father to stand alongside him at the head of Yeshivat Har Etzion, so that the institution would be led by a Torah role model of the highest caliber.

Despite their differences, they found common ground in many areas, among them a shared vision regarding the mission of the Hesder yeshivot. The difference between them, in form not in essence, is demonstrated in R. Amital’s well-known expression of his worldview through a short Hasidic story, while my father encapsulated his philosophy through a complex, twenty-page scholarly essay. Nonetheless, the ideas are one and the same.

R. Amital would often relate the tale of Rav Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the Ba’al HaTanya, who lived for a time in a modest dwelling with his son and infant grandson. The house had three rooms: The Ba’al HaTanya sat and learned in the innermost room; in the middle room sat his son, later known as the Mitteler Rebbe, also learning; and in the outer room, the infant lay in his cradle. During his study, the Ba’al HaTanya heard the infant crying, and, as he passed through the middle room, noticed that his son was so engrossed that he did not hear the baby. After comforting the child, he rebuked his son: “If one learns Torah and does not hear the cry of a child, there is a flaw in his learning.”

R. Amital’s message about personal responsibility is clear. My father’s article expresses a similar worldview: One who studies Torah without national responsibility, one who learns without combining study with acts of kindness, one who walls himself inside the four cubits of the beit midrash and does not hear the needs of the Jewish People—his Torah is deficient. A moral obligation lies on every person, and certainly every Torah scholar, to shoulder responsibility for society. Since in the State of Israel the existential and security threat stands at the forefront of our national challenges, yeshiva students must take part in addressing it.....

Mayer Lichtenstein, Rav of Beit Knesset Ohel Menachem in Beit Shemesh, is a Ram at Yeshivat Orot Shaul in Tel Aviv. This essay (translated by Jeffrey Saks) is excerpted from his newly released Musar Avi: Shiurim Be’ikvei Torat Avi Mori HaRav Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l.

READ MORE OF THIS FASCINATING MAN :

https://traditiononline.org/the-complexity-of-hesder-revisited/?