"Kollel should be a meritocracy — a place for the few who are truly

destined for scholarship, not a refuge for the unwilling. Torah learning

should inspire men to serve, to build, to defend, to uplift."... Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz/ Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky - Zechuso Yagen Aleinu.

In the long history of Jewish survival, few ideas have caused more internal rot than the postwar fantasy that every Jewish man is meant to study Torah full-time. It is not a mitzvah — it is a distortion. It has become the greatest Jewish fraud since the end of World War II.

The Torah commands us to be a “kingdom of priests” — not a nation of dependents. Our ancestors were shepherds, merchants, craftsmen, judges, warriors, and prophets — men who lived and worked in the real world, sanctifying it through their deeds. Yet somewhere after the Holocaust, a tragic inversion took hold. The noble dream of rebuilding the Torah world turned into an ideology of isolation, dependency, and cowardice — all sanctified in the name of “learning.”

After the Holocaust, Torah scholarship in Europe lay in ruins. The yeshivos of Lita and Galicia, the centers of Jewish intellectual and spiritual greatness, were reduced to ash. It was natural — even holy — that survivors sought to resurrect the world that was destroyed. But rebuilding Torah did not mean abandoning reality.

Rabbi Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, the visionary founder of Yeshiva Torah Vodaath in New York, and Torah Umesorah, presently, a network of 760 Orthodox schools

throughout the United States, whose mission is to ensure that every

Jewish child in Yeshivos, day schools, and Bais Yaakovs receives the

highest standards of Torah education, along with the skills to lead a successful life and become a productive member of society.

Rabbi Mendlowitz understood this clearly. He was no small-time educator; he was a prophet of postwar Jewish survival. His dream was not to create an army of cloistered scholars, but a generation of American Jews who would combine Torah fidelity with productive citizenship. He sent his students into Jewish education, business, and communal leadership. He taught that Torah must illuminate the world, not retreat from it.

Had his philosophy prevailed, American and Israeli Orthodoxy might have looked very different today. But in the chaos of postwar Europe and the birth of the State of Israel, another current — quieter, more insidious — gained ground.

When David Ben-Gurion was negotiating the contours of the new Jewish state, he met with the Chazon Ish, Rabbi Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz, the spiritual titan of the Lithuanian yeshiva world. The Chazon Ish insisted that Torah study must remain free from state interference and that a small number of young men — around 400 — should be exempted from military service to rebuild the ranks of Torah scholars decimated by the Nazis.

Ben-Gurion, ever the pragmatist, agreed. It was a small concession — a symbolic gesture — to the old world that had perished. He never imagined that this modest arrangement would metastasize into a political juggernaut, protecting hundreds of thousands of men from national service and labor.

That meeting in 1947 was the original sin of the “status quo.” It institutionalized the separation of Torah from life. It legitimized the idea that Torah scholars could live on the public dime while other Jews bore the burden of defending and sustaining the state.

What began as a few hundred exceptions turned into an ideology: full-time study for all men, indefinitely. The kollelim that once trained the elite became welfare networks for the masses. The word “Torah world” ceased to mean a culture of ethical refinement and began to mean a bureaucracy of stipends, exemptions, and ignorance of reality.

The Agudath Israel movement, originally formed in Europe to preserve traditional Judaism against secular Zionism, found a new purpose in this arrangement. In prewar Poland, Agudah had been wary of aligning Torah with political power; in postwar Israel, it became addicted to it.

Agudah’s rabbis realized they could leverage the collective bloc of their yeshiva students and their growing families to extract power from the state. Knesset seats translated into subsidies for yeshivos. Subsidies sustained the illusion of holiness without responsibility. The system fed itself: poverty bred more dependence, which bred more loyalty.

And so, a movement that once feared secular politics became one of its most skilled manipulators. Its moral language masked a cynical machine. “Daas Torah” — the supposed divine authority of rabbis over all matters — was weaponized to silence dissent and perpetuate control.

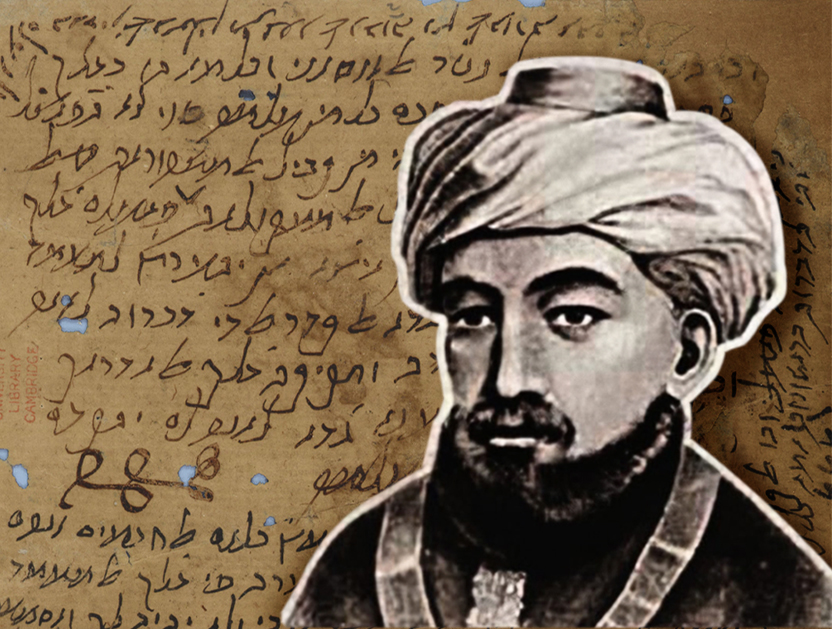

Meanwhile, the Rambam’s ancient words — “Anyone who decides to study Torah and not work, and supports himself from charity, desecrates God’s name” — were quietly erased from the curriculum.

In America, Rabbi Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz’s Torah Vodaath sent out a different message. He encouraged his students to engage the world, to teach, to lead, to work. He famously said: “The Torah must live in America — not hide in America.”

But his philosophy lost the postwar struggle. By the late 1960s, the myth of the “full-time learner” became the new gold standard of Jewish virtue. A young man who entered business or education was considered lesser. The kollelnik became the symbol of piety — even as his wife struggled to feed the children and his community depended on the charity of others.

The fraud was spiritualized: “You work for money,” the kollelnik was told, “but I work for Heaven.” It was a seductive lie — because it cloaked laziness in holiness, irresponsibility in sacrifice.

The true Torah ideal, as Rabbi Mendlowitz and the Rambam understood, was to live in the world and sanctify it. The Torah was not meant to be the privilege of the idle but the compass of the active.

Today, in 2025, Israel pays the price of this seventy-year-old deception. Nearly half of Israel’s Haredi men do not participate in the workforce. Entire neighborhoods thrive on government stipends and foreign donations. Military service exemptions are defended as divine law.

And yet, when war comes — as it did on October 7 — it is not the yeshiva world that runs toward the fire. It is the sons of secular kibbutzim, Modern Orthodox families, and immigrants from Ethiopia and Ukraine who fill the ranks. The Torah world hides behind the soldiers it despises.

This is not faith. This is fraud.

A Torah that forbids its followers from defending their people is a Torah that has been hijacked. A Torah that turns charity into lifetime welfare is not Torah lishmah — it is Torah le-hafsidah, a Torah that corrodes from within.

And the spiritual cost is even greater. Generations of young men grow up believing that work is shameful, that reality is impure, and that holiness lies in detachment. The Torah becomes not a light to the nations but a dark room to hide in.

It does not have to be this way. The Torah world can still be redeemed — but only by returning to its authentic roots. The path forward is not rebellion but restoration.

Restore the balance between Torah and derech eretz — learning and labor — as Hillel, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, and the Rambam all lived. Restore the honor of the Jewish worker, soldier, and builder — as Yehoshua, David, and Nechemiah all embodied. Restore the vision of Rabbi Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, who believed that Torah should sanctify the world, not escape it.

"Kollel should be a meritocracy — a place for the few who are truly destined for scholarship, not a refuge for the unwilling. Torah learning should inspire men to serve, to build, to defend, to uplift." Rabbi Mendlowitz declared. Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky agreed.

The Torah that once built nations has been reduced to a subsidy. The Torah that gave us courage has been turned into a comfort blanket. It’s time to tear off the blanket and reclaim the sword.

The idea that every Jewish man must sit in yeshiva indefinitely is not holiness — it is heresy against the Torah’s purpose. It betrays the essence of what it means to be Jewish: to act, to serve, to create, to take responsibility.

Seventy years of moral decline began with a simple deal — a “status quo” that turned exception into entitlement. Ben-Gurion gave the Chazon Ish 400 exemptions. We now live with 400,000. That is not continuity — that is collapse.

The time has come to end the fraud — not by abandoning Torah, but by rescuing it. Torah must once again be the soul of a living nation, not the slogan of a parasitic sect.

|

| REPUBLISHED |

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/full-time-torah-study-for-all-the-greatest-orthodox-jewish-fraud-running-steady/