|

| EZRIEL TAUBER VIOLATED HILCHOS YICHUD AT EVERY TURN - THE ONE MAN BEIS DIN, MARRIAGE COUNSELOR, MARRIAGE THERAPIST, DAYAN, TOEN, ONE ON ONE WITH WOMEN ALWAYS! HE TOLD THE WOMEN TO COME ALONE! WHEN I CALLED HIM ABOUT ONGOING ALLEGATIONS AGAINST HIM BY MANY MARRIED WOMEN (KOLO D'LO PASUK - BY DIFFERENT WOMEN OF DIFFERENT AGE GROUPS) - HE DENIED HE EVER MET OR KNEW THE WOMEN INVOLVED! | | |

|

THE MOMENT HAS ARRIVED (TO STOP PEDDLING FRAUDULENT INSANITY!)

By Yonoson Rosenblum |

An interview with Rabbi Zev Cohen of Chicago's Special Beis Din dealing with issues of abuse

Chicago's Rav Zev Cohen was on the job less than five years when

he first became aware that abusers were preying on members of his

community. He was advised by daas Torah to establish a special beis din

to deal with the issue. Three decades later, the success of that effort

bears significance for the wider Torah world.

When I started thinking about how the Torah community can

avoid repeating the traumatic events of the past few weeks, I kept

coming back to one name: Rabbi Zev Cohen, the rav of Adas Yeshurun, one

of the principal anchors of the West Rogers Park neighborhood of

Chicago. With five kollelim from early in the morning until late in the

evening, the voice of Torah is constantly heard in the shul.

Over the years, Rabbi Cohen has alerted me to many threats to our

communities — the casual entry of cannabis into our celebrations, the

dangers of the Internet — all of which he has spoken about loudly and

forcibly in multiple forums.

But the reason that I thought about him now is that approximately 30

years ago, he played a pivotal role in the establishment of the first

standing beis din to deal with abuse issues — the "Special Beis Din."

The Beis Din does not intend or attempt to substitute for law

enforcement, but it has carved out a vital role of its own , using its

intimate knowledge of the community to deny perpetrators access to past

victims or potential future ones.

For years, Rabbi Cohen has been campaigning for communities across

America to establish such batei din, and throughout our lengthy

conversation, he reiterated frequently that he agreed to speak to

Mishpacha in the hope of advancing the communal discussion on the topic.

How did the "Special Beis Din" come into existence?

About 30 years ago, the local mikveh association, Daughters of

Israel, had a one-day event for women. At the end of the program, there

were a number of breakout sessions, one of which dealt with the trauma

of childhood abuse. The organizers expected a handful of women to show

up for that. But more than 80 women attended that session. That was the

wake-up call.

I was a young rabbi, less than five years in my position, and I did

what I always did when I needed the guidance of genuine daas Torah — I

called my rosh yeshivah, Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock ztz"l, the Long Beach

Rosh Yeshivah. He advised me to set up a beis din to deal with the

issue. So I spoke to the two senior rabbinic figures in Chicago at the

time, whose authority spanned all the segments of the Orthodox

community: the Chicago Telshe Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Avrohom Chaim Levin

ztz"l; and Rav Gedaliah Schwartz ztz"l, av beis din of the Rabbinical

Council of America and head of the Chicago Rabbinical Council.

They both agreed to serve as dayanim for such a beis din. We were

also joined by Rav Shmuel Fuerst, a close talmid of Rav Moshe Feinstein

and a nationally recognized posek and dayan. The prestige and authority

of the dayanim would prove invaluable over the years in establishing

communal trust in the beis din.

Did such a beis din exist elsewhere in the United States? Did you

have any precedents in rabbinic literature for the Special Beis Din?

As far as we could ascertain, there were no such batei din then

existing in North America, and perhaps in the world. The issue of

molestation is barely mentioned in the teshuvah literature. And the

leaders of the previous generation, Rav Moshe Feinstein ztz"l and Rav

Yaakov Kamenetsky ztz"l, were no longer alive to guide us. That is just

one of the reasons that the presence of a highly respected rosh yeshivah

and dayanim was so crucial to the beis din's success.

How did you get the word out about the existence of the Special Beis Din?

First, we contacted shul rabbanim, school principals, and therapists

within the community. In the early years of the beis din, there were two

high-profile cases, involving multiple victims, and our handling of

those cases brought the existence of the beis din to public notice.

Just let me interject here that one of the things for which I've been

campaigning a long time is that every community have a hotline, like

the mental health hotlines that already exist, to which victims or their

family members can call. The existence of such a hotline does two

things. First, it sends a message to victims that the community takes

their suffering very seriously and wants to help them. And second, it

lets perpetrators know that there are mechanisms in place that make it

likely they will be discovered. That, in turn, makes it much harder for

them to tell victims, "No one will believe you."

We have found that the fear of discovery, and the communal outcry

that goes with it, is often a deterrent. It appears that the way the

Special Beis Din has dealt with the cases has had a positive impact in

reducing the instances of abuse. For instance, after our most

high-profile case, in which we were forced to take a very public stand

to stop the abuse, our caseload has dropped off considerably.

Before we talk about how the Special Beis Din works, can I just ask: Why don't you just tell victims to go to the police?

If a victim tells us that she wants to go to the police, she receives

our encouragement. But frequently, victims are too traumatized to

testify to the police, and find it easier to speak to rabbanim. In

addition, it is important to remember, one cannot just go to the police

and have someone thrown in jail. We had one case where the victim wanted

to go to the police. The accused immediately posted bail and was soon

back on the streets. But at that point, we could no longer impose our

own restrictions on the perpetrator, because the police were already

involved.

How does the Special Beis Din decide whether the accusations are

true or not? What is your standard of proof? It is clearly something

much less than the two eidim, subject to rigorous cross-examination.

The standard that we apply is nikarim divrei emes — in other words,

does the testimony of the victims have all the markers of truth. There

are a number of instances in halachah in which a beis din can impose

punishments to remove a threat to the community without the testimony of

two witnesses. The Rambam paskens, for instance, that the beis din, in

every place and every time, has the power to impose lashes on someone

about whom there is a nonstop kol that he is involved in arayos [Hilchos

Sanhedrin 24:5].

In the halachic literature, there are discussions of the degree of

proof needed for the community to turn someone over to the authorities

when that person — e.g., a counterfeiter — represents a threat that

could bring punishment on the entire community.

I think it is important to know that over the past 30 years, there

was only one case in which the accused denied the charges. In every

other instance, there were multiple victims who testified, and the

predators admitted what they had done as soon as we confronted them with

the accusations.

I've had the feeling in many cases that the perpetrators were

relieved to be caught and subject to restrictions that would prevent

them from repeating their behavior. The Special Beis Din always imposes

the requirement of undergoing therapy on the predator, though it never

assumes that therapy by itself is adequate protection for the community.

What happens after the victim's testimony and the perpetrator's confession?

In formulating the restrictions to be imposed on the perpetrator, we

first work together with local mental health professionals, who have

ongoing relationships with state and city authorities. We present the

accused with a set of carefully crafted requirements to which he must

conform. That means that the perpetrator must be removed from all the

circumstances and situations in which he had contact with his victims.

And we try to ensure that he will never be in a place where his victims

will see him. That has even included telling a father or a grandfather

that he cannot attend his daughter's or granddaughter's wedding. Cases

where siblings or other family members are considered a threat are

obviously the most complicated, and require extreme sensitivity on the

part of the Special Beis Din, working in conjunction with mental health

professionals.

The perpetrator may be barred from the men's mikveh and not allowed

into shul without a constant shadow. And the permission to attend shul

may be conditioned on leaving prior to the kiddush, and never departing

from the area of prayer at any time. All those responsible for the

places from which the perpetrator is barred or limited will be informed

of the restrictions in place.

It is crucial that the perpetrator knows that he is being observed.

And further, that if he violates the conditions we have set for him, the

entire community will be alerted as to his deeds and his failure to

comply with our restrictions. That remains a powerful deterrent even

after the passage of much time.

Something I've been speaking about for years is the necessity of a

national data bank of abusers so that they cannot just leave one place

and return to their former ways in another city. We once had a case

where we found out that someone on our lists had taken a job as a

mashgiach for a Pesach program. Baruch Hashem, we were successful in

having him removed before the program started, but a national database

of shuls and organizations, like Agudah, Orthodox Union, and Young

Israel, would have protected against him being hired in the first place.

I would guess the Special Beis Din is not exactly like we

normally picture a beis din, with the two parties, both standing before

the dayanim?

That is true. Just the sight of the perpetrator is often traumatizing

for a victim, even if many years have elapsed since the abuse occurred.

Unless one has personally had experience with abuse victims, it is

impossible to understand the pain that they experience. They will

require therapy, often for many years. The trauma continues to plague

them for years to come, and unless dealt with, it is likely to result in

lifelong struggles.

Many victims do not come forward for years out of feelings of shame

and the fear that if anyone finds out about what happened to them, they

will not be able to make a shidduch and the like.

The Torah explicitly equates violations of a woman to murder: "for

like a man who rises up against his fellow and murders him, so is this

thing" [Devarim 22:26]. And in some ways it is even worse than murder, because of the enduring pain.

A perpetrator once told me that he wanted to apologize to his victim.

I told him that although there is a place for sincere apology, for what

you have done, even if you prostrated yourself on the ground before the

victim in a puddle of tears, it would not be nearly enough. An apology

is for when you back up and break your neighbor's headlight.

In formulating your remedies, what are your priorities?

Our first priority is the well-being of the victims, doing whatever

is possible to help them overcome their pain. For instance, we may often

ban the perpetrator from attending simchahs and other communal events

where he or she might see the victim, and thereby cause them to relive

what they went through.

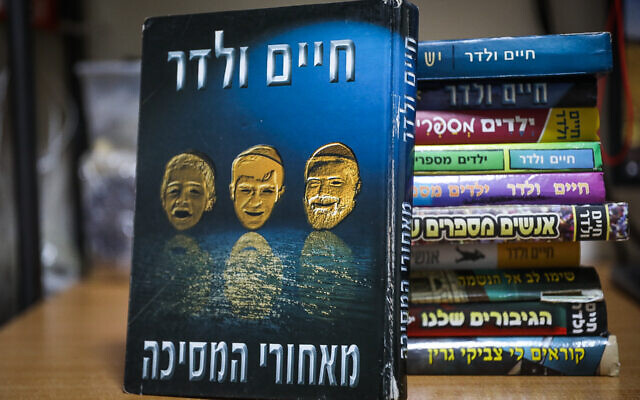

Klal Yisrael are described as rachmanim bnei rachmanim. And no one

has more claim on our sympathy than victims. Over the last two weeks,

for instance, I've been asked repeatedly whether it is necessary to

remove from one's house the works of a certain author accused in front

of a beis din. I'm not going to pasken for the entire world as to what

they should or should not do on this matter. But I'm begging parents who

feel they must retain the books to at the very least cover them and put

them in a box or in the basement out of sight.

You have no idea who is going to come to your home and what they

might have gone through. I was told about a woman who is today a teacher

in a frum school and was herself a victim. She described walking into

her school library and seeing the works of said author still prominently

displayed. For her it was like a punch in the gut, absolutely

devastating. In the immediate aftermath of the same story, I received

calls from two victims who told me that they were re-traumatized just by

the publicity surrounding the whole case.

The second priority, which goes hand in hand with the first, is ensuring that there are no further victims.

And a distant third is trying to assist the family of the

perpetrator. There is nothing to be gained by unnecessarily depriving

the perpetrator of all livelihood. If he owns a business or store that

brings him into constant contact with potential victims, obviously he

cannot continue in the store. But if he works in the back office, there

is little sense in forcing the employer to fire him and leaving the

family as a burden on the community.

Have your efforts generally been supported by the community?

To be effective, a Special Beis Din needs the support of the entire

community. If the batei din that I envision are going to come into

being, the initiative needs to come from both rabbanim and balabatim.

Such batei din require communal resources to function effectively.

Have you also found yourself subjected to criticism?

Who is not subject to criticism? (Unfortunately, I bear the scars to

prove it.) Usually, the criticism has been: Why weren't you tougher on

the perpetrator? Why didn't you just go to the police?

In general, our relationship with the police has been excellent. The

statute governing mandated reporters has changed frequently in recent

years, but that issue has been negotiated by a group of frum therapists

who have good relationships with the police.

It is a mistake, however, to think that the police will be more

successful than we have been in stopping the scourge of abuse. The

police have told us on many occasions that we are much better positioned

than they are to supervise the perpetrator, by virtue of our

familiarity with the milieu of the perpetrator and victim. What's a

mikveh? Where does the perpetrator daven, and what other situations are

ancillary to synagogue attendance? The police know nothing about such

things.

As I mentioned above, we support those victims who want to go to the

police. I've testified in court in several cases where young men, now in

their mid-twenties, have brought damage actions against those who

abused them. Sadly, most of those plaintiffs are no longer observant,

another indication of the devastation abuse has on the souls of victims.

Reb Zev, thank you so much for taking the time to speak to us about this vital subject.

Let's just hope that the moment has finally arrived, as a consequence

of the recent tragedies, for every medium-sized community to establish

its own Special Beis Din, and for the smaller communities to be

organized to refer to batei din in larger nearby cities. And that this

conversation will serve as a catalyst for that.

ROSENBLUM WILL CLAIM I VIOLATED COPYRIGHT LAWS - TAKE A SCREENSHOT BEFORE HE GETS GOOGLE TO TAKE IT DOWN!

https://www.jewishmediaresources.com/2155/the-moment-has-arrived

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/SCGYAGQ6ZBBRHNTUYW37CO3Q3E.JPG)