The shock of Friday’s catastrophe at Mount Meron is still raw.

The graves of the victims, including the children killed in the crush,

are still fresh. Yet the debate over what it all means for the country

and for Haredi society has already begun.

A few overpowering facts, not least that nearly all the victims

were Haredi, are driving an unusual new introspection, and leading the

major media outlets of the community to turn against one of its

characteristic traits: its longstanding and much-criticized “autonomy”

from the Israeli state.

Haredi Israelis are simultaneously part of and apart from broader

Israeli society. Making up as much as 12 percent of the Israeli

population, the community is not uniform; different sects and

subcultures interact in very different ways with the state and with

other subgroups. While the “autonomy,” as Israelis often refer to the

phenomenon, does not encompass all Haredim, it encompasses enough of the

community to be — so growing numbers of Haredim now believe — a serious

problem.

One sees the autonomy in studies of Israel’s cash economy that point

to mass tax evasion in the Haredi community; in routine clashes with

police in parts of Mea Shearim, Beit Shemesh, and other places; in the

refusal to take part in national service; in school networks that refuse

to teach the basic curriculum taught in non-Haredi schools; and, most

recently, in the refusal of many Hasidic sects over the past year to

obey pandemic lockdowns.

Ultra-Orthodox Jews gather at the

gravesite of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai at Mount Meron in northern Israel

on April 29, 2021, as they celebrate the Jewish holiday of Lag B’Omer.

It is a community that talks about itself in the language of

weakness, always a street scuffle or political squabble away from talk

of “decrees,” “persecution,” and “antisemitism.” Proposals for welfare

cuts or calls to introduce more math education in their schools are

described in Haredi media in terms borrowed from czarist oppression in

Eastern Europe.

That rhetoric of weakness and victimhood has a purpose: to cloak

or perhaps to justify the opposite reality. As a group, Haredim are not

weak. They are powerful enough to constantly expand and defend their

separate school systems, to found towns and neighborhoods for their

communities, to maintain a kind of self-rule that forces Israeli

politicians to literally beg Haredi rabbinic leaders — usually

unsuccessfully — to adhere to coronavirus restrictions.

The story of the Meron disaster cannot be divorced from this

larger story of Haredi autonomy, from the Haredi habit of establishing

facts on the ground that demonstrate their strength and independence,

and then crying “persecution” when those steps are challenged.

The strange meaning of ‘spontaneous’

In the two days that have passed since the disaster, investigators

and journalists have uncovered a despairingly long litany of warnings

from past years about the safety problems at the Meron site. State

comptroller reports, police site analyses, dire admonitions by earnest

safety officials in Knesset hearings — all fell on deaf ears.

These records reveal that if the Mount Meron site had hosted any

other kind of event — a rock concert or a political rally — then police

safety regulations would have limited attendance to roughly 15,000

people. Friday’s event saw more than 100,000 in attendance.

Men covered with prayer shawls at Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai’s grave in Meron. October 11, 2017 (David Cohen/ Flash90/ File)

They reveal, too, that Israeli officials simply do not believe it is

possible to demand such limitations from the Haredi community.

As one former senior cop told the Yedioth Ahronoth daily over the

weekend, “If a safety engineer from the police, in their last

inspection of the site before the commemoration, would have tried to

shutter the Toldot Aharon courtyard [where the disaster occurred] — do

you believe that decision would have been enforced? … Not even the chief

of police can do that. If someone tries, that’s their last job in the

police.”

Haredi political parties, acting at the behest of Haredi religious leaders, would have made sure of it.

As journalist Nadav Eyal noted in his Yedioth Ahronoth column on

Sunday, the Meron festival was officially classified by the police as a

“spontaneous religious event.” It’s a preposterous term for the

gathering. It’s not just that the Lag B’Omer festival takes place in

highly non-spontaneous fashion on a known holiday (i.e., Lag B’Omer) but

it also constitutes the largest annual religious gathering in the

country.

Months of planning go into it. Its many different lots and bonfire

ceremonies and musical performances are carefully divvied up among the

competing sects and religious endowments that run the pilgrimage.

Thousands of ultra-Orthodox Jews

celebrate the lighting of a bonfire during celebrations of the Jewish

holiday of Lag B’Omer on Mt. Meron in northern Israel on April 29, 2021.

The government spends a small fortune each year on stages,

grandstands and chartered buses from Haredi towns. And each year, a

half-dozen government agencies all try to take credit.

So when police label the event “spontaneous,” they do not mean that

it is literally spontaneous. It is a way to acknowledge that the police

have no control over the event, that they could not impose attendance

caps or infrastructure standards even if legally required to.

On Thursday, hours before the disaster, Interior Minister Aryeh Deri

bragged to the Haredi radio station Kol Hai that he had successfully

prevented Health Ministry officials from limiting the number of

attendees over coronavirus fears. Deri lamented that the professional

echelon at the ministry did not grasp that attendees would be protected

by the spiritual influence of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, the

second-century sage commemorated at the Meron festival.

Shas party head Aryeh Deri casts his vote in the general elections in Jerusalem on March 23, 2021.

“The government clerks don’t understand,” he said. “This is a holy

day, and the largest gathering of Jews [each year].” Bad things, he

suggested, don’t happen to Jews on religious pilgrimage: “One should

trust in Rabbi Shimon in times of distress.”

Even as he bragged of his and the Haredi community’s political power,

he then deployed, instinctively, the rhetoric of victimhood. He urged

listeners “to pray for the world of Torah and for Judaism, which are in

danger. They’re in great danger.”

An end to the autonomy?

Children were crushed to death at Meron. Hardened paramedics wept on

television. When cellular networks on the mountain went down, fearful

families were reduced to sharing photographs of their missing loved ones

on social media in a desperate attempt to make contact. One rescuer

described to reporters the moment he had to yell at a tormented

colleague to stop trying to resuscitate a child: “It was hopeless, and

we had to try to resuscitate others.”

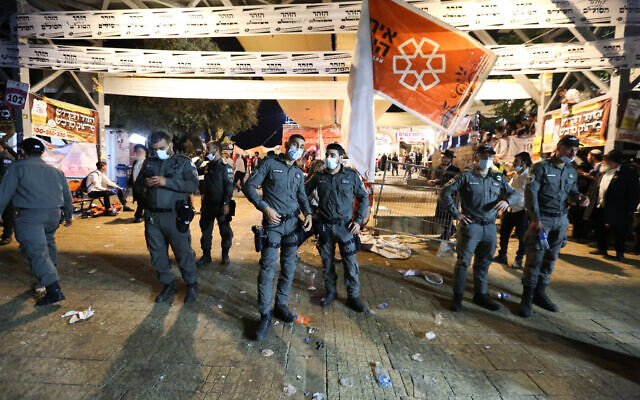

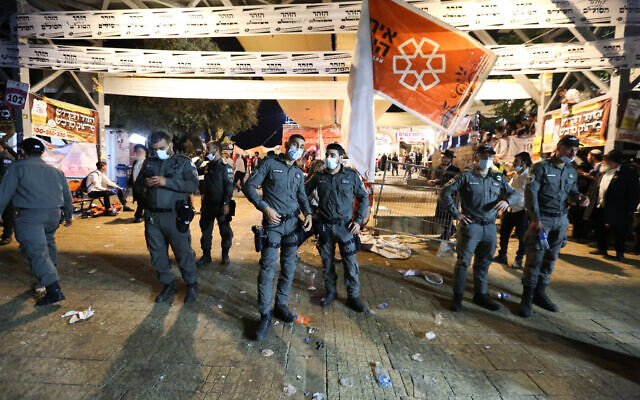

Rescue forces and police at the scene

after a mass fatality scene during the celebrations of the Jewish

holiday of Lag B’Omer on Mount Meron, in northern Israel on April 30,

2021.

No complaint from secular Israel could make Haredi society question

the strange autonomous bubble it had constructed as a cultural defense

against the state’s modernizing influence, nor the power of the Haredi

rabbis and their courts, whose egos and squabbles had divided the holy

site into disconnected courtyards and helped drive Friday’s deadly

chaos. But the shattering images from Meron cut through the glib

self-assurance and silenced, at least for the moment, any boasts about

Haredi self-rule.

And as the confident voices dwindled into shocked silence, other

voices came to the fore, cries of angry self-critique that are rarely

heard from the mainstream of Haredi society.

The voices all carried a single message: The state’s kowtowing to our leaders has brought this disaster upon us.

A hat at the scene of a deadly crush

during the Jewish holiday of Lag B’Omer on Mt. Meron, in northern Israel

on April 30, 2021

Yossi Elituv, editor of Mishpacha, the largest-circulation Haredi

weekly, urged his followers not to focus only on police errors or lack

of government oversight.

“Our community also has a duty to learn lessons,” he wrote on Friday.

The first lesson: That the state must step in and end the chaos. “Our

first and immediate task is to free the mountain from the control of the

[religious] endowments…. The state needs to establish a professional

authority to run the site….Take the mountain away from the endowments

and confer on it the status of the Western Wall, with zero tolerance for

rule-breaking.”

On Sunday morning, Elituv followed up with a four-word tweet: “State investigative committee, now!”

Moty Weinstock, an editor at the Haredi weekly Bakehilla, reached the same conclusion.

“Any solution at Meron that amounts to less than bringing order to

the entire mountain, canceling the religious endowments and dismantling

all the areas designated [to specific sects] will ensure the horrifying

images come back,” he declared.

On social media, in other newspapers, including the Hasidic mainstay

daily Hamevaser, and in countless media interviews, Haredi Israelis

asked the same questions and leveled the same complaints.

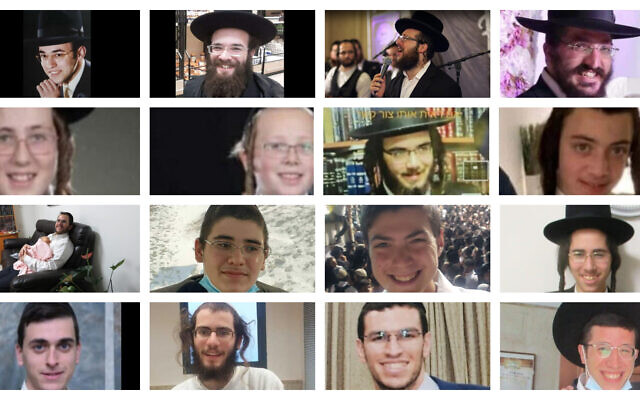

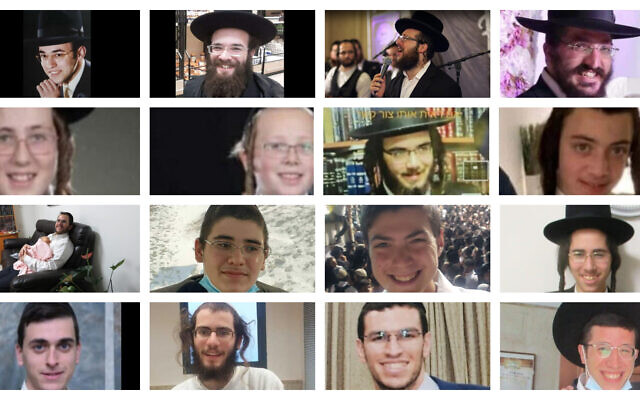

Top row (L-R): Menahem Zakbah, Simcha

Diskind, Shraga Gestetner, Shimon Matalon; 2nd row (L-R): Moshe Natan

Neta Englard, Yehoshua Englard, Yosef David Elhadad, Moshe Mordechai

Elhadad; 3rd row (L-R): Haim Seler, Yedidia Hayut, Daniel (Donny)

Morris, Nahman Kirshbaum; 4th row (L-R): Abraham Daniel Ambon; Yedidya

Fogel, Yisrael Anakvah, Moshe Ben Shalom

A community that had convinced itself it could flout the demands of

state authorities has suddenly and with growing confidence and

earnestness begun to cry out for “order” and “authority,” to demand that

the state impose its control, the rabbinic courts’ pride and vanity be

damned.

New assumptions

Contrary to its most basic claim about itself, Haredi Judaism is

neither rigid nor unchanging. New ideas filter in, old ones are

reinterpreted. Scholars of Haredi life speak of profound changes across a

broad spectrum of cultural and social mores, from a growing number of

Haredim in higher education, in the workforce and in the military to new

roles for women and new political loyalties that are collectively

driving the community into ever deeper integration with mainstream

Israeli society.

Yet change requires one underlying condition: It must happen quietly.

Assumptions shift unacknowledged, new practices are treated as old and

commonplace.

Take Haredi Zionism as an example. Ten years ago, the Shas party

formally declared itself a Zionist party and joined the World Zionist

Organization. But the declaration was whispered, not shouted. Today, no

Shas voter would believe that until a decade ago the party would not

officially call itself Zionist and had avoided joining Zionist

institutions.

It’s the same story on the Ashkenazi side. Twenty years ago,

Ashkenazi Haredim in Israel refused to acknowledge the ceremonies

conducted at military cemeteries on Memorial Day. The military rituals

were borrowed from other nations, they complained. Jews must commemorate

in their own ancient ways. Then, over the course of the past decade,

without fuss or fanfare or explicit acknowledgment of any kind, United

Torah Judaism politicians have taken to officiating at those very

ceremonies as official representatives of the Israeli government,

standing alongside pants-clad female soldiers and laying wreaths at

concrete memorials.

Haredi society can change with the times, as long as it does not admit the change aloud.

Ultra-Orthodox Jews wearing prayer shawls

gather next to a bonfire, as they take part in prayers next to the

grave of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai during Lag B’Omer celebrations at Mt.

Meron in northern Israel, early Thursday, May 10, 2012

In 2018, just after he took part in that year’s Lag B’Omer pilgrimage

to Meron, Haredi journalist Aryeh Erlich tweeted his concerns about a

certain narrow walkway at the site: “The narrow exit path that leads

from the bonfire ceremony of the Toldot Aharon [Hasidic sect] creates a

human bottleneck and terrible shoving, to the point of an immediate

danger of being crushed. And it’s the only exit…. They must not hold the

bonfire at that site again before they open a wide and well-marked

exit.”

Erlich’s tweet went viral on Friday, exactly three years too late.

In an interview Sunday with the Tel Aviv-area radio station 103 FM

about the disaster he predicted so precisely, Erlich rejected any blame

directed at Haredi society for the deaths.

“How can you blame the Haredi public?” he demanded. The Meron pilgrimage “is a tradition that’s been going on for 550 years.”

Then who was to blame? “It’s the police that approve the event. There

are clear regulations. No event can take place without a safety

officer, a policeman who signs off on it and approves it, and that’s

what happened at Meron.”

There’s a “sovereign,” he added. That sovereign “decided to ignore

[the danger], chose shoddy improvisation instead, and failed to impose

safety standards. The Haredi political parties are victims here; it’s

not serious for the police to now say that because of [the Haredi

parties] they didn’t do what they were supposed to do. The police are

supposed to enforce the law.”

Israeli rescue forces and police at a

mass fatality scene during celebrations of the Jewish holiday of Lag

B’Oomer on Mt. Meron, in northern Israel on April 30, 2021.

It is a pivot in expectations that by its very denial of Haredi

culpability signals the shift away from Haredi autonomy. Erlich couches

his critique as a defense of Haredi political leaders. But even here,

with the blame directed exclusively at the Israel Police, the argument

is the same: The police no longer have the right to ignore safety rules

merely because Haredi religious sects demand it. How dare the state risk

the lives of its Haredi citizens by allowing Haredi autonomy to trump

their safety?

The catastrophe at Meron will not lead any in the community to

question other elements of its separate existence, such as its

independent school system. Nothing so fundamental will change from a

single tragedy.

But those now asking the state and the police to take

over at Meron, those now questioning, openly and not-so-openly, their

leaders’ wisdom and their community’s ethos of separation, will apply

that lesson to other things in the future.

https://www.timesofisrael.com/after-meron-calamity-haredim-question-the-price-of-their-own-autonomy/?utm_source=The+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=daily-edition-2021-05-03&utm_medium=email