New Tel Aviv University study finds that Facebook and WhatsApp have significantly altered the attitude of the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community toward sexual abuse

by Judy Siegel-Itzkovich | May 10, 2021 | Medical Miracles

The head of the ultra-Orthodox United Torah Judaism party on Wednesday threw his backing behind the establishment of a state commission of inquiry into the deadly crush at a religious festival last month that killed 45 people, including many children.

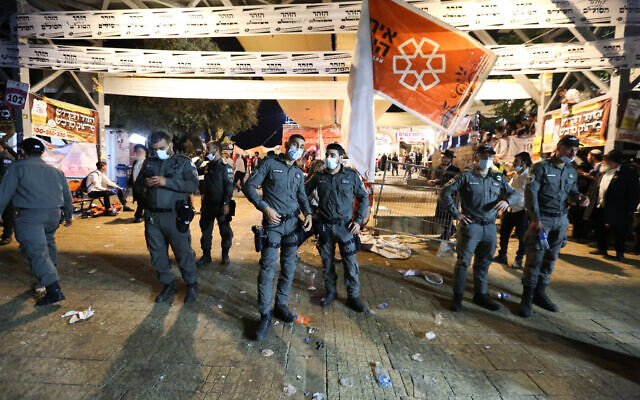

No arrests have been made since the April 30 tragedy, the deadliest civilian disaster in Israel’s history, which is being investigated by the Israel Police.

UTJ MK Moshe Gafni chairs the Knesset Finance Committee, which held a session Tuesday on the disaster during Lag B’Omer celebrations at Mount Meron in northern Israel. In a letter to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, he said the parliamentary committee agreed the “correct way” to proceed is to form an official commission of inquiry, which would be led by a Supreme Court justice.

Gafni also said he would chair further committee meetings on the matter “so we can offer solutions for the future so a case like this will not happen again.”

“I also believe that this is the right way to obtain a legal

solution regarding the sanctuaries and ownership at Meron, as well as

comfort for the families of the dead,” he wrote in the letter.

He asked Netanyahu to have the government begin advancing a proposal to establish a state commission that will investigate the disaster and “make recommendations that will allow for the regulation of the site in terms of halacha [Jewish law], engineering and safety.”

It was unclear if Netanyahu would allow a proposal to form a commission come before the government for approval. While the premier has said he backs a thorough investigation, he has not taken up calls to back an official state commission of inquiry.

Wednesday’s letter appeared to mark a reversal for Gafni, whose party is part of Netanyahu’s right-wing religious bloc. Gafni suggested during Tuesday’s meeting that a committee led by the chief rabbi be formed to address the problems at Meron, drawing some ridicule.

Also Wednesday, the centrist Yesh Atid party — which is seeking to replace Netanyahu as prime minister following the March elections — said it would seek to fast-track a bill to form a state commission to investigate the disaster during a vote next week, suggesting possible cross-bloc support.

Earlier this month, Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit announced that a joint investigative team from the Israel Police and the Justice Ministry’s Police Internal Investigations Department will lead a probe into the deadly incident.

Police and the PIID had already launched independent probes. State Comptroller Matanyahu Englman has also announced that he will investigate.

There have been increasing demands for a state commission of inquiry into the tragedy, with the focus directed at the organization of the annual Lag B’Omer events at Mount Meron.

The disaster, which began around 1 a.m. on April 30 near the gravesite of the second-century sage Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, took place when huge crowds of ultra-Orthodox pilgrims were making their way along a narrow walkway with a slippery metal flooring that ended in flights of stairs. People began to slip and fall, others fell upon them, and a calamitous crush ensued.

The site, the second-most visited religious site in Israel after the Western Wall, has become an extraterritorial zone of sorts, with separate ultra-Orthodox sects organizing their own events and their own access arrangements, with no overall supervision and with police routinely pressured by cabinet ministers and ultra-Orthodox politicians not to object.

|

| Nobel Putz Awardee ----- MK Moshe Gafni at a conference in Jerusalem |

Former police officials have said there had been fears for years that tragedy could strike as a result of the massive crowds and lack of supervision on Lag B’Omer.

Multiple reports in Hebrew media outlets indicated that there had been immense pressure by religious lawmakers ahead of the festivities to ensure that there would be no limits placed on the number of attendees due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some 100,000 mostly ultra-Orthodox pilgrims ultimately attended the event. A framework drawn up by the Health Ministry, in consultation with other government officials, police and others, would have limited the event to 9,000 participants but was not implemented.

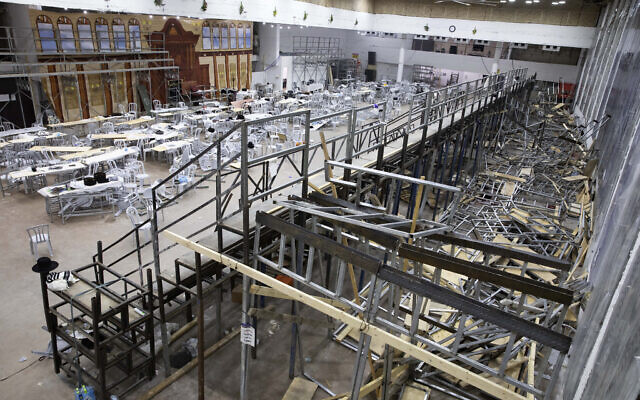

In another incident on Sunday, two people were killed and 167 injured, including five seriously, when a bleacher collapsed under celebrants in a Givat Ze’ev synagogue just before the start of the Shavuot festival on Sunday evening.

Two people were killed and 167 injured, including five seriously, when a bleacher collapsed under celebrants in a Givat Ze’ev synagogue just before the start of the Shavuot festival on Sunday evening.

A video showed the ultra-Orthodox Karlin synagogue in the West Bank settlement, just north of Jerusalem, packed with male worshipers when the bleacher suddenly collapsed.

The wounded were taken to hospitals in Jerusalem. Medics and firefighters confirmed there were no people trapped beneath the bleacher after searching the area.

Magen David Adom said medics treated five people who were seriously injured, along with 10 people in moderate condition and 152 who suffered light injuries.

Medics later confirmed the deaths of a 40-year-old man and a 12-year-old boy. They were not immediately identified.

Some large ultra-Orthodox events feature bleachers, known as “tribunas” in Israel, which are packed with standing or dancing parishioners surrounding a central table where community leaders are seated.

The father of one of the injured told the Kan public broadcaster that just ten minutes before the collapse, attendees were told in a safety announcement to stop pushing one another.

Defense Minister Benny Gantz said his heart went out to the victims. “IDF forces led by the Home Front Command and the Air Force are working to assist in the evacuation. I pray for the safety of the wounded,” he said.

The synagogue is located in an incomplete building and had not been approved for use, the police commander of the Jerusalem District told reporters.

Documents published by the Kan public broadcaster showed the police and the Givat Ze’ev municipality trying to enforce an order banning Shavuot services at the unfinished Karlin synagogue.

In the documents, police warned the local council about the danger of allowing services at the building, which did not have an occupancy permit. However, when the local council asked police to step in to enforce the closure, police responded that it was the council’s job.

A spokesperson for the police told Channel 13 News that the force plans to investigate the deadly collapse.

The incident came 16 days after the Meron disaster, in which 45 people were crushed to death during a mass gathering of mainly ultra-Orthodox Jews to celebrate the Lag B’Omer holiday at Mount Meron.

The Meron tragedy — Israel’s deadliest civilian peacetime disaster — occurred as thousands streamed through a narrow walkway at the southern exit of the Toldot Aharon compound on the mountain. The walkway was covered with metal flooring and may have been wet, causing some people to fall underfoot during the rush for the exit. Some apparently fell on the walkway and down a flight of stairs at its end, toppling onto those below and precipitating a fatal crushing domino effect.

Since the disaster, several former police chiefs have characterized Meron — Israel’s second-most visited Jewish holy site after the Western Wall — as a kind of extraterritorial facility. It was administered by several ultra-Orthodox groups, while the National Center for the Protection of Holy Places, part of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, apparently had some responsibility over it as well, as did the local authority, and the police. But ultimately, no single state body had full responsibility.

Even the heroes of Labor like Yitzchak Rabin and Yigal Allon came to be exposed more over time. It had been years since Rabin had played his evil role during the perfidious criminal murdering of Irgun heroes on the Altalena, patriots who had risked their lives to bring weapons to take Jerusalem in 1948, but Rabin returned with perfidy to push through the Oslo disaster. The Oslo Accords laid the foundation for Arafat to control whole swaths of Judea and Samaria, to gain political autonomy and control over mass media, educating two new generations of Arab children to hate and murder Jews, and owning an internal security and police apparatus. Allon, meanwhile, had helped form the party that idealized Josef Stalin and later mourned the death of mass murderer Yosef Stalin, but later split from it to form the Achdut Haavoda party.

Ariel Sharon, too, now is dead but his legacy lives on in the thousand Hamas rockets fired indiscriminately at civilians throughout Israel. Sharon unilaterally took Israel out of Gaza without a plan for The Day After, expelled 8,600 pioneering brave Jews from their homes, handed over to the Arabs thriving industries and gorgeous shuls and yeshivot, and let them all burn as he turned his attention next “kadimah” — to the east, to wreak the same havoc for Judea and Samaria. Only a massive stroke, and then yet another, stopped The Bulldozer from bulldozing more Jews out of their homes. Was his termination the hand of G-d or a stroke of luck? You be the judge.

That is what aggregated to cause today’s catastrophe. That — plus a Netanyahu hesitancy - admittedly in the face of world condemnation and Iranian threats - to fight to a complete and outright victory.

Prof. Daniel Pipes has been advocating “Victory” these past several years, the idea that nothing short of an actual bruising crushing unequivocal victory over Hamas terror will achieve long-term results. By contrast, Netanyahu has followed a “lawn mowing” philosophy: every few years, as new Hamas weeds grow, Israel has to “mow the lawn.” Netanyahu is here, of course, bearing the brunt of daily decisions and Pipes is a theoretician.

However, the two competing perspectives each carries its respective pros and cons. A “Victory” campaign will entail the risk of more casualties up-front and even worse international condemnation. By contrast, “Mowing the Lawn” reduces deaths in battle for the short term and limits ICC “war crimes” investigations initially but so far assures more deaths and more world condemnations later, as future wars erupt. Know that these “Operations” — Operation Cast Lead, Operation Protective Edge, Operation Guardian of the Walls — are not “operations” but are full-blown, but short, wars.

Responding to one thousand rockets fired into civilian centers in Paris and Marseille, London and Manchester, Berlin and Hamburg, Rome and Milan, Shanghai and Beijing, Moscow and St. Petersburg, Los Angeles and New York — that is war, not an “operation.”

Amid such catastrophes, Israelis vote every so often — with emphasis these past two years on “often” — and, as happens in every democratic electorate, certain regions tend to vote in certain ways. For example, in America the Northeast tends towards the Democrats and the left while the Deep South goes Republican conservative. Similarly in Israel, those in Judea and Samaria, those in the northern border development towns, Jerusalemites and those near and amid the Gaza “envelope” vote for the military security of a Likud-right bloc, those in Jerusalem, Bnai Brak, Elad and Beit Shemesh also veer towards religious parties.

Those in the Gush Dan-Tel Aviv region where cafes serve seafood and worse while brazenly open on Shabbat, tend to vote for Labor and Meretz on the left. Thus, a leftist Ron Huldai can get elected and reelected mayor of Tel Aviv forever — at 23 consecutive years, already twice the tenure of the Netanyahu “too long” premiership — but when he tried to form a national political party to contend for the premiership over all of Israel’s voters he was handed his head in a hand basket unceremoniously

Meanwhile, for decades Israel’s third largest city a bit more north has been known as “red Haifa” for its more extreme leftist sympathies..

Perhaps Tel Aviv and Haifa voters felt they could vote gaily and merrily for the Left because it never was their necks on the line as rockets roared nightly from Gaza into Sderot, Ashkelon, and Ashdod. Haifa leftists, although on the receiving end of katyushas during the Lebanon Wars, did not share the concerns of residents based in Maalot and Kiryat Shmona who contend with Hezbollah on their border.all the time. The Arab riots in Haifa may serve as a rude awakening.

All things come to an end. Decades of Oslo-based governmental blunders driven by myopic leftist Labor governments, and by Sharon-Olmert Kadimah blindness, now have synergized to bring the catastrophe of a Hamas-dominated Gaza in the south whose Hamas terror rockets now do reach Tel Aviv, even as Hezbollah yet awaits demonstrating to Haifa’s Meretz leftists what lies in store there.

Moments like these change a nation. The fall of the Twin Towers in Manhattan showed liberal New Yorkers that they, too, can be hit. They ended up shocked into voting for another decade of Republican mayors, and the American country stuck with George W. Bush for the next eight years.

If Israel is forced to go to fifth elections in three or four months, it may well be expected that the present catastrophic awakening — that Hamas now can, will, and does hit Tel Aviv — and the Israeli Arab riots - will move some extra seats to the right. More than that, it will change a generation of Jewish thinking in Israel among the dwindling remnant of leftists who did not already wise-up after two intifadas.

There is no making peace with people who will not accept the right of Jews to live sovereign in the land of Israel. It is a hard pill to swallow, recognizing impossibly that there is no possible formula for making peace with such other than utter crushing. The reason that German Nazis under Hitler and Eichmann finally have stopped their effort to destroy us is that they are dead, crushed, annihilated, wiped out. Even their carcasses are gone. The reason that Japan, who destroyed Pearl Harbor, became friendly to and a great ally of America can be explained in eight syllables: Na-ga-sa-ki-Hi-ro-shi-ma.

As with Oslo and the intifadas, this catastrophe will impact another cohort of leftist Israelis for years to come. Tel Aviv and Haifa will be a bit less red, even less pink. And there may come a time when, beyond mowing the lawn, the weeds finally will be extirpated because they must be.

Rabbi Prof. Dov Fischer is adjunct professor of law at two prominent Southern California law schools, Senior Rabbinic Fellow at the Coalition for Jewish Values, congregational rabbi of Young Israel of Orange County, California, and has held prominent leadership roles in several national rabbinic and other Jewish organizations. He was Chief Articles Editor of UCLA Law Review, clerked for the Hon. Danny J. Boggs in the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and served for most of the past decade on the Executive Committee of the Rabbinical Council of America. His writings have appeared in The Weekly Standard, National Review, Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, Jerusalem Post, American Thinker, Frontpage Magazine, and Israel National News. Other writings are collected at www.rabbidov.com

It is always easy to dismiss the warnings. No one wants to think anything he or she does puts him or her in danger. In order to live in the world, we all need to turn a willfully blind eye to the many ways harm may possibly come to us. We can’t know all the statistics about the ordinary things that may cause us harm like our chances of being hit by a car or a stray bullet, of having our homes and possessions destroyed in a hurricane, contracting a deadly virus that spreads easily in unventilated spaces or having a fatal coronary attack. It would be too overwhelming.

But we also can’t ignore the warning signs.

Like the verse in the book of Micah 3:11 which reads,”The LORD is in our midst; No calamity shall overtake us,” it is much easier to assume that if one is doing something appropriate and in an attempt to reach God and worship God, that nothing bad can happen. Unfortunately, as we all know from the events on Lag B’Omer at Mount Meron in Israel, that is far from the case. Bad things can overtake us in all kinds of places.

In fact, the portion of the verse I just quoted is only the latter part of it. The first part discusses the corruptness of the rulers, priests and prophets and the problem that they assume they can rely on God, smugly stating that whatever they do they will be fine because after all “God is in our midst.”

I don’t know whether God was at Meron, and there is no virtue in the ability to see perfectly clearly in hindsight. But on Meron, the warnings were clear as reported here and here. Tragically no one was able to decide who had the final oversight on the site of the celebration at Mount Meron, so the festive atmosphere became a mournful one. Now, Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi David Lau is calling for the state to have oversight, as reported here.

There are so many everyday dangers that are easier to ignore; no one wants to live in a state of constant anxiety over the potential for accidents and awful things to happen. But as anyone who has parented a mobile baby or toddler knows, one has to anticipate as much as possible where danger lies so it can be averted. Will the child run wherever he can, even into a street full of speeding traffic if a parent is not holding his hand tightly? Will she eat the object of a size potential to choke her if it is left in the vicinity of her grasp? Will she wander too close to the edge of a body of water if I don’t notice where she is going before she drowns? There are sadly, many tragic childhood accidents, some preventable and some not, yet most children make it through those early years unscarred.

Likewise, someone in the state of Israel needs to take that position and have final responsibility for safety evaluations at holy sites and celebrations and as well as the authority to implement the recommendations.

In Mecca, after a similarly tragic stampede, the authorities instituted a lottery system for pilgrims so that the amount of people participating each year would be within the limits of safety. As reported here, the Saudi government sets quotas, allocated to those of different countries. Perhaps at Meron, if 100,000 celebrants want to attend each year and the site only has space for 10,000, then attendance should be limited for each individual to once every 10 years. It could certainly be done.

If we want to bring God into our midst, we can’t rely on the corrupt assumptions of our belief that evil won’t befall us. It is a longstanding Jewish tradition that we are enjoined not to rely on miracles as a matter of course. In an apt comparison to the case of Meron, the Talmud in Kiddushin 39b is speaking about a boy who goes up a ladder to shoo a mother bird away from her young before taking the chicks, as commanded in Deuteronomy 22:7. The Torah says that the reward for this mitzvah, shooing the mother away is length of days: if the boy is killed in the process of performing this command, how can our system of faith cope with it? The Talmud asks, “But didn’t Rabbi Elazar say that those on the path to perform a mitzva are not susceptible to harm, neither when they are on their way to perform the mitzva nor when they are returning from performing the mitzva?” The response given there is that “it was a rickety ladder, and therefore the danger was established; and anywhere that the danger is established one may not rely on a miracle.”

It should be clear that the danger of the site at Meron was established numerous times by safety monitors from various regional and police groups. The site itself was a rickety ladder; no one had any business relying upon a miracle to celebrate there without such a catastrophe as finally occurred. I hope that going forward this teaching “anywhere that danger is established one may not rely on a miracle” becomes more elevated than the wrong one of “the Lord is in our midst, no evil will befall us.” Each of us needs to be aware of danger so that it can be safely averted.

http://thewisdomdaily.com/was-the-tragedy-at-meron-preventable/

by Judy Siegel-Itzkovich | May 10, 2021 | Medical Miracles

The ultra-Orthodox (haredi) Jewish community in Israel and abroad has largely avoided discussion of sex for many decades. Many even in their late teens or very-early 20s get married after being brought together by a professional matchmaker and a few short meetings, learning about sexual relations just a few weeks from a rabbi or female counsellor.

As a result of their “innocence, there have been numerous reports of sexual abuse by rabbis and other male adults in ritual baths and yeshivot, even some cult groups in which “very observant religious leaders” assemble a harem of women who produce many children.

One of the most shocking stories recently was when the founder of the voluntary Israeli organization Zaka (the Disaster Victim Identification group) – who as a young man was anti-Zionist, organized violent demonstrations and then turned into a highly respected pro-Zionist activist who was nearly awarded the Israel Prize, was uncovered by the press as an alleged rapist and molester that the insular community refused to report to the authorities for decades. A month ago, he attempted suicide and has suffered severe brain damage.

But the absolute silence is coming to an end. A new study from Tel Aviv University (TAU) reveals a significant change over the past decade in the haredi community’s attitudes toward sexual abuse – after many years of silencing and concealment, covering up and repressing the issue.

The study, conducted by Dr. Sara Zalcberg of TAU’s religious studies program in the Entin Faculty of Humanities, was presented at the “Haredi Society in Israel” conference of Shandong University (one of the oldest and prestigious universities in China, it was founded in 1901) and TAU’s Joint Institute for Israel and Judaism Studies.

Zalcberg said that “deep processes occurring in this sector over the past few years as a result of exposure to the media and to higher education, point to a rise in awareness of the consequences of sexual abuse for its victims, as well as the need for therapeutic intervention and prevention of future abuse.”

“The study’s findings indicate a trend of significant change in the haredi society’s attitude toward sexual abuse,” she continued. “About a decade ago, many of the victims in this sector were not even aware of the fact that they had been sexually abused; Many parents didn’t know that sexual abuse of children even existed. Haredi society as a whole was characterized by a three-way culture of silence – involving the victim, his/her family and the community and leadership. According to our study’s findings, this ‘conspiracy of silence’ has gradually weakened in recent years, with evidence for a significant rise in both awareness and discourse regarding sexual abuse and its consequences.”

The study was based on interviews with professionals working with the haredi population, including cases of sexual abuse, as well as activists involved in community safety, parents of children who had been sexually abused and a woman who had been sexually abused herself when she was a child.

According to Zalcberg, the study has identified a gradual process, starting with the exposure of the haredi sector to the job market, education and the virtual world, alongside the emergence of grassroots activism from inside haredi society. These have engendered a growing openness in discourse about sexuality, the body and intimacy, as well as an increase in the numbers of therapeutic and welfare professionals coming from the community – ultimately generating the first cracks in the high walls of reluctance to admit and address sexual abuse in Haredi society.”

The team found that the changes are manifested in several ways. First, a growing and unprecedented use of the online arena, including WhatsApp and Facebook, for discussing and addressing sexual abuse. One interviewee in the study noted: “The haredi sector is exposed to the Internet, and once exposed to it they are exposed to everything. Information is more accessible.”

A social worker in an ultra-Orthodox city added: “Haredi women in the therapeutic professions use the Internet to disseminate information about sexual abuse, safety and therapy, and so the haredi community learns about the issue.”

The study also identifies change among families and parents of victims, reflected in the demand for prevention workshops that provide tools for recognizing and preventing sexual aggression. The supreme value of defending the community against any outside influence or criticism is being replaced by care for the welfare of families and children. This change has also led to a conceptual shift in a large portion of the haredi leadership, who now recognize the abuse and its victims and promote the connection with welfare authorities.

Zalcberg stresses that the change can be discerned even in the more insular and conservative groups within haredi society. As Chezi, a haredi social worker working with the ultra-Orthodox haredi population in one of the social services, commented: “We see more openness even in the conservative community. Hassidic communities that usually don’t turn to us to the social services now come when there’s a case of sexual abuse. They understand that this is a serious matter.”

At the same time, as the study points out, despite the significant processes taking place in haredi society, there are still considerable gaps in both awareness and addressing the phenomenon and its consequences. “Despite the change taking place in haredi society with regard to discussing and addressing sexual abuse, a great deal more still needs to be changed,” Zalcberg concluded. “Both discourse and awareness should be enhanced, preventive measures must be advanced, and the rates of reporting abuse and asking for professional intervention should be increased. There is urgent need for mapping families and communities who don’t have sufficient access to information and services, and for promoting specifically tailored responses.”

https://www.israel365news.com/190402/new-tel-aviv-university-study-finds-that-facebook-and-whatsapp-have-significantly-altered-the-attitude-of-the-ultra-orthodox-jewish-community-toward-sexual-abuse/

That victory required national cohesion, voluntary sacrifice for the common good and trust in institutions and each other. America’s response to Covid-19 suggests that we no longer have sufficient quantities of any of those things.

In 2020 Americans failed to socially distance and test for the coronavirus and suffered among the highest infection and death rates in the developed world. Millions decided that wearing a mask infringed their individual liberty.

This week my Times colleague Apoorva Mandavilli reported that experts now believe that America will not achieve herd immunity anytime soon. Instead of largely beating this disease it could linger, as a more manageable threat, for generations. A major reason is that about 30 percent of the U.S. population is reluctant to get vaccinated.

We’re not asking you to storm the beaches of Iwo Jima; we’re asking you to walk into a damn CVS.

Americans have always been an individualistic people who don’t like being told what to do. But in times of crisis, they have historically still had the capacity to form what Alexis de Tocqueville called a “social body,” a coherent community capable of collective action. During World War I, for example, millions served at home and abroad to win a faraway war, responding to recruiting posters that read “I Want You” and “Americans All.”

That basic sense of peoplehood, of belonging to a common enterprise with a shared destiny, is exactly what’s lacking today. Researchers and reporters who talk to the vaccine-hesitant find that the levels of distrust, suspicion and alienation that have marred politics are now thwarting the vaccination process. They find people who doubt the competence of the medical establishment or any establishment, who assume as a matter of course that their fellow countrymen are out to con, deceive and harm them.

This “the only person you can trust is yourself” mentality has a tendency to cause people to conceive of themselves as individuals and not as citizens. Derek Thompson of The Atlantic recently contacted more than a dozen people who were refusing to get a Covid-19 vaccine. They often used an argument you’ve probably heard, too: I’m not especially vulnerable. I may have already gotten the virus. If I get it in the future it won’t be that bad. Why should I take a risk on an experimental vaccine?

They are reasoning mostly on a personal basis. They are thinking about what’s right for them as individuals more than what’s right for the nation and the most vulnerable people in it. It’s not that they are rebuking their responsibilities as citizens; it apparently never occurs to them that they might have any. When Thompson asked them to think in broader terms, they seemed surprised and off balance.

The causes of this isolation and distrust are as plentiful as there are stars in the heavens. But there are a few things we can say. Most of the time distrust is earned distrust. Trust levels in any society tend to be reasonably accurate representations of how trustworthy that society has been. Trust is the ratio of the times someone has shown up for you versus the times somebody has betrayed you. Marginalized groups tend to be the most distrustful, for good reasons — they’ve been betrayed.

The

other thing to say is that once it is established, distrust tends to

accelerate. If you distrust the people around you because you think they

have bad values or are out to hurt you, then you are going to be slow

to reach out to solve common problems. Your problems will have a

tendency to get worse, which seems to justify and then magnify your

distrust. You have entered a distrust doom loop.

A lot of Americans have seceded from the cultural, political and social institutions of national life. As a result, the nation finds it hard to perform collective action. Our pathetic Covid response may not be the last or worst consequence of this condition.

How do you rebuild trust? At the local level you recruit diverse people to complete tangible tasks together, like building a park. At the national level you demonstrate to people in concrete ways that they are not forgotten, that someone is coming through for them.

Which brings us to Joe Biden. The Biden agenda would pour trillions of dollars into precisely those populations who have been left out and are most distrustful — the people who used to work in manufacturing and who might now get infrastructure jobs, or the ones who care for the elderly. This money would not only ease their financial stress, but it would also be a material display that someone sees them, that we are in this together. These measures, if passed, would be extraordinary tangible steps to reduce the sense of menace and threat that undergirds this whole psychology.

The New Deal was an act of social solidarity that created the national cohesion we needed to win World War II. I am not in the habit of supporting massive federal spending proposals. But in this specific context — in the midst of a distrust doom loop — this is our best shot of reversing the decline.

We’re in the middle of yet another reckoning with abuse in the Jewish community.

The Forward reported last week that a former senior leader of the Reform movement had sexually assaulted members of his congregation and may have committed other acts of abuse and harassment — and that the Reform movement may have kept details of this misconduct from the public.

It’s likely that this news may be the first of many revelations across the Jewish world in the coming weeks and months, particularly as the Union for Reform Judaism launches an independent investigation into sexually inappropriate conduct that may have occurred under its watch.

These are critical conversations. We must talk about clergy who sexually abuse, and the people and institutions that cover for them.

But our grappling with the issues in Jewish sacred leadership cannot and must not end there.

Our conversations about healthy leadership, appropriate boundaries, appropriate modeling of spirituality and non-toxic theology cannot, and should not, begin and end with the question, “Is this person a sexual abuser?”

We also must talk about clergy who — even outside any context of sexual abuse — manipulate. Who gaslight. Who abuse the teacher-student power dynamic.

The clergy who blur emotionally necessary lines between themselves and those who rely on them for spiritual learning and guidance. This kind of fuzziness is a problem, regardless of whether or not it’s sexual.

The ones who let you in, just a little too much. Who don’t just encourage you to open up, but maybe push a little too far. Who say things like, “You can trust me!” “You’re really special, you know.” “I don’t want to play it safe.”

About the clergy who do that trick of staring into your eyes, deeply, to make you feel so seen — and then tell you what they want you to do.

The clergy who are energy vampires.

The ones who lower boundaries around touch — even if they never cross the line into legally-defined harassment or assault.

The ones who, even if they are not sexual abusers themselves, learned how to be clergy from abusers, have abusers as role models and pass on abusive approaches and tactics to their students.

The ones who will say things to you privately that they might deny having said in public.

The ones who offer what seems to be a narrative about spirituality, but is really a story about ego.

Whose Torah, sermons and teaching reflect a toxic worldview, one that doesn’t honor congregants’ agency, selfhood and intuition.

The clergy who teach that spirituality is all about warm, pleasant feelings, who do not help you to do the hard, painful work that a true spiritual practice also demands. This is a concept known as spiritual bypassing — defined concisely by Rabbi Rachel Barenblat as the wrongful use of “spirituality to justify avoidance of things that are painful or uncomfortable, like anger or conflict or boundaries.” Often, it comes hand-in-hand with an eliding of boundaries, a rush towards forgiveness without accountability, a denial of the need to speak difficult truths, a drive to pretend that situations are healthy or safe when, in fact, they may not be.

In many ways, it’s more difficult to talk about these behaviors, because they are less concrete than instances in which we can say, “This person said or did such-and-such specific thing.” And goodness knows getting to the place where we can name sexual abuse has not been simple work, and we’re not even fully there.

We are in no way done with reckoning with sexual abuse by clergy or the systemic overhaul now needed — and long needed — to address that abuse. Silence breakers are heroes.

And, at the same time, we must talk about these other clergy problems. I have seen all the above issues manifest in a single leader. I’ve also seen many leaders who do one or two of them.

Those who are in lay leadership need to learn to identify toxic leadership styles among clergy, and to meaningfully address them. Even if the leaders, and the toxic styles they use, can be inspiring. Even if they make you feel good.

And those of us who are clergy need to be honest in facing the question of how we may have blurred these lines ourselves.

When our egos have gotten a little too inflated by the work of teaching Torah.

When our own unhealed wounds or emotional needs have slipped into the driver’s seat, often without us even noticing.

When our burnout has prompted us to lean harder than we should on others to help pick up the slack.

What ideas have we absorbed about what holding space in ritual looks like? About how to touch people’s souls when preaching? About communicating compassion in pastoral counseling? About what our communal norms should be for creating connection?

Where did we learn those ways of doing and being? Who do those ideas serve? And who do they empower? What tools do we have to discern that?

We have barely begun to deal with the sexual predators in our midst; there are many more yet to be revealed, and many more still who will likely never be outed. We have not yet begun to identify the people who cause this other, non-sexual kind of boundary abuse, or even come up with a way to name it.

We must also ask these other questions, grapple with them, if we want our sacred spaces to be healthy, to truly serve God and our communities. This, too, is our work.

https://forward.com/opinion/468977/rabbis-sexual-misconduct-judaism-reform/

Jewish people were blamed for spreading disease, and considered expendable victims.

Last year, I felt lucky to be an American in Germany. The government carried out a comprehensive public-health response, and for the most part, people wore masks in public. More recently, COVID-19 cases have surged here, with new infections reaching a single-day zenith in late March. Germany has lagged behind the United States and the United Kingdom in vaccination efforts, and German public-health regulators have restricted use of the AstraZeneca vaccine to people over 60, after seven cases of rare cerebral blood clots. Key public-health measures, particularly lockdowns and vaccination, have been divisive. Among some people, even the magnitude of the virus’s infectious threat has been in question.

Over the past year, Germany’s sprawling anti-lockdown movement has brought together a disquieting alliance of ordinary citizens, both left- and right-leaning, and extremists who see the pandemic response as part of a wider conspiracy. In August, nearly 40,000 protesters gathered in my neighborhood to oppose the government’s public-health measures, including the closure of stores and mask mandates. It was unnerving to hear German chants of “Fascism in the guise of health” from my window, and all the more given that the same day, a subgroup of those protesters charged Parliament. In a moment presaging the U.S. Capitol insurrection, 400 German protesters, including a group carrying the Reichsflagge, emblematic of the Nazi regime, rushed past police and reached the building’s stairs. Germany is riddled with QAnon adherents, some of whom are anti-vaccination, and some people are using this pandemic to articulate their anti-Semitic beliefs. They might deny COVID-19 exists, then play it down, and eventually blame 5G and Jewish people for the pandemic. In Bavaria, vaccine skeptics now use messages such as “Vaccination makes you free,” an allusion to “Work makes you free,” a horrific maxim of Nazi concentration camps.

Like the United States, Germany has a thriving anti-vaccination movement, and here it has encompassed conspiracy theorists, left-leaning spiritualists, and the far right. These last ties are the most troubling. In German-speaking lands, anti-science sentiment, right-wing politics, and racism have been entwined since even before Jews were accused of spreading the bubonic plague in the 14th century. These movements illustrate a grim truth: In both the past and the present, anti-science sentiments are inextricably tangled with racial prejudice.

Anti-vaccine movements are as old as vaccines, the scholar Jonathan M. Berman notes in his book, Anti-vaxxers, and what is striking, according to the author, is that early opponents at the turn of the 18th century believed that vaccination was “a foreign assault on traditional order.”

But beliefs linking anti-science sentiment and anti-Semitism were already deeply set. During the plague outbreak of 1712 and 1713, for instance, the city of Hamburg initiated public-health measures including forbidding Jews from entering or leaving the city, Philipp Osten, the director of Hamburg’s Institute for History and Ethics of Medicine, told me. By the time cholera emerged in the 19th century, sickening thousands of people in the city within a matter of months, these antiquated ideas had taken on a new form.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE:

My daughter called me before the Sabbath in terrible pain. Beyond trying to process the deaths of religious Jews at Mount Meron on Lag Ba’omer, she was in an argument on a chat group with a woman who said that the deaths had a reason.

The shock of Friday’s catastrophe at Mount Meron is still raw. The graves of the victims, including the children killed in the crush, are still fresh. Yet the debate over what it all means for the country and for Haredi society has already begun.

A few overpowering facts, not least that nearly all the victims were Haredi, are driving an unusual new introspection, and leading the major media outlets of the community to turn against one of its characteristic traits: its longstanding and much-criticized “autonomy” from the Israeli state.

Haredi Israelis are simultaneously part of and apart from broader Israeli society. Making up as much as 12 percent of the Israeli population, the community is not uniform; different sects and subcultures interact in very different ways with the state and with other subgroups. While the “autonomy,” as Israelis often refer to the phenomenon, does not encompass all Haredim, it encompasses enough of the community to be — so growing numbers of Haredim now believe — a serious problem.

One sees the autonomy in studies of Israel’s cash economy that point to mass tax evasion in the Haredi community; in routine clashes with police in parts of Mea Shearim, Beit Shemesh, and other places; in the refusal to take part in national service; in school networks that refuse to teach the basic curriculum taught in non-Haredi schools; and, most recently, in the refusal of many Hasidic sects over the past year to obey pandemic lockdowns.

It is a community that talks about itself in the language of weakness, always a street scuffle or political squabble away from talk of “decrees,” “persecution,” and “antisemitism.” Proposals for welfare cuts or calls to introduce more math education in their schools are described in Haredi media in terms borrowed from czarist oppression in Eastern Europe.

That rhetoric of weakness and victimhood has a purpose: to cloak or perhaps to justify the opposite reality. As a group, Haredim are not weak. They are powerful enough to constantly expand and defend their separate school systems, to found towns and neighborhoods for their communities, to maintain a kind of self-rule that forces Israeli politicians to literally beg Haredi rabbinic leaders — usually unsuccessfully — to adhere to coronavirus restrictions.

The story of the Meron disaster cannot be divorced from this larger story of Haredi autonomy, from the Haredi habit of establishing facts on the ground that demonstrate their strength and independence, and then crying “persecution” when those steps are challenged.

In the two days that have passed since the disaster, investigators and journalists have uncovered a despairingly long litany of warnings from past years about the safety problems at the Meron site. State comptroller reports, police site analyses, dire admonitions by earnest safety officials in Knesset hearings — all fell on deaf ears.

These records reveal that if the Mount Meron site had hosted any other kind of event — a rock concert or a political rally — then police safety regulations would have limited attendance to roughly 15,000 people. Friday’s event saw more than 100,000 in attendance.

They reveal, too, that Israeli officials simply do not believe it is possible to demand such limitations from the Haredi community.

As one former senior cop told the Yedioth Ahronoth daily over the weekend, “If a safety engineer from the police, in their last inspection of the site before the commemoration, would have tried to shutter the Toldot Aharon courtyard [where the disaster occurred] — do you believe that decision would have been enforced? … Not even the chief of police can do that. If someone tries, that’s their last job in the police.”

Haredi political parties, acting at the behest of Haredi religious leaders, would have made sure of it.

As journalist Nadav Eyal noted in his Yedioth Ahronoth column on Sunday, the Meron festival was officially classified by the police as a “spontaneous religious event.” It’s a preposterous term for the gathering. It’s not just that the Lag B’Omer festival takes place in highly non-spontaneous fashion on a known holiday (i.e., Lag B’Omer) but it also constitutes the largest annual religious gathering in the country.

Months of planning go into it. Its many different lots and bonfire ceremonies and musical performances are carefully divvied up among the competing sects and religious endowments that run the pilgrimage.

The government spends a small fortune each year on stages, grandstands and chartered buses from Haredi towns. And each year, a half-dozen government agencies all try to take credit.

So when police label the event “spontaneous,” they do not mean that it is literally spontaneous. It is a way to acknowledge that the police have no control over the event, that they could not impose attendance caps or infrastructure standards even if legally required to.

On Thursday, hours before the disaster, Interior Minister Aryeh Deri bragged to the Haredi radio station Kol Hai that he had successfully prevented Health Ministry officials from limiting the number of attendees over coronavirus fears. Deri lamented that the professional echelon at the ministry did not grasp that attendees would be protected by the spiritual influence of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, the second-century sage commemorated at the Meron festival.

“The government clerks don’t understand,” he said. “This is a holy day, and the largest gathering of Jews [each year].” Bad things, he suggested, don’t happen to Jews on religious pilgrimage: “One should trust in Rabbi Shimon in times of distress.”

Even as he bragged of his and the Haredi community’s political power, he then deployed, instinctively, the rhetoric of victimhood. He urged listeners “to pray for the world of Torah and for Judaism, which are in danger. They’re in great danger.”

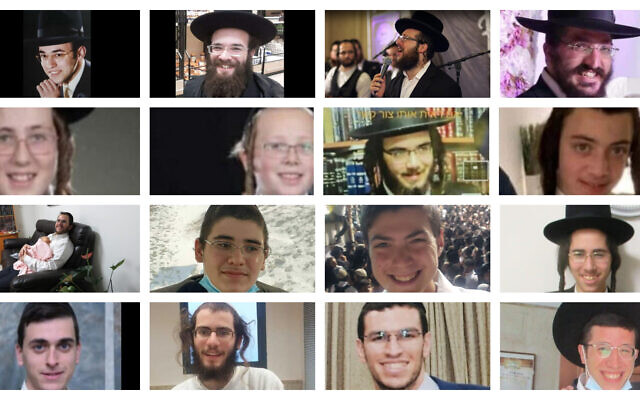

Children were crushed to death at Meron. Hardened paramedics wept on television. When cellular networks on the mountain went down, fearful families were reduced to sharing photographs of their missing loved ones on social media in a desperate attempt to make contact. One rescuer described to reporters the moment he had to yell at a tormented colleague to stop trying to resuscitate a child: “It was hopeless, and we had to try to resuscitate others.”

No complaint from secular Israel could make Haredi society question the strange autonomous bubble it had constructed as a cultural defense against the state’s modernizing influence, nor the power of the Haredi rabbis and their courts, whose egos and squabbles had divided the holy site into disconnected courtyards and helped drive Friday’s deadly chaos. But the shattering images from Meron cut through the glib self-assurance and silenced, at least for the moment, any boasts about Haredi self-rule.

And as the confident voices dwindled into shocked silence, other voices came to the fore, cries of angry self-critique that are rarely heard from the mainstream of Haredi society.

The voices all carried a single message: The state’s kowtowing to our leaders has brought this disaster upon us.

Yossi Elituv, editor of Mishpacha, the largest-circulation Haredi weekly, urged his followers not to focus only on police errors or lack of government oversight.

“Our community also has a duty to learn lessons,” he wrote on Friday. The first lesson: That the state must step in and end the chaos. “Our first and immediate task is to free the mountain from the control of the [religious] endowments…. The state needs to establish a professional authority to run the site….Take the mountain away from the endowments and confer on it the status of the Western Wall, with zero tolerance for rule-breaking.”

On Sunday morning, Elituv followed up with a four-word tweet: “State investigative committee, now!”

Moty Weinstock, an editor at the Haredi weekly Bakehilla, reached the same conclusion.

“Any solution at Meron that amounts to less than bringing order to the entire mountain, canceling the religious endowments and dismantling all the areas designated [to specific sects] will ensure the horrifying images come back,” he declared.

On social media, in other newspapers, including the Hasidic mainstay daily Hamevaser, and in countless media interviews, Haredi Israelis asked the same questions and leveled the same complaints.

A community that had convinced itself it could flout the demands of state authorities has suddenly and with growing confidence and earnestness begun to cry out for “order” and “authority,” to demand that the state impose its control, the rabbinic courts’ pride and vanity be damned.

Contrary to its most basic claim about itself, Haredi Judaism is neither rigid nor unchanging. New ideas filter in, old ones are reinterpreted. Scholars of Haredi life speak of profound changes across a broad spectrum of cultural and social mores, from a growing number of Haredim in higher education, in the workforce and in the military to new roles for women and new political loyalties that are collectively driving the community into ever deeper integration with mainstream Israeli society.

Yet change requires one underlying condition: It must happen quietly. Assumptions shift unacknowledged, new practices are treated as old and commonplace.

Take Haredi Zionism as an example. Ten years ago, the Shas party formally declared itself a Zionist party and joined the World Zionist Organization. But the declaration was whispered, not shouted. Today, no Shas voter would believe that until a decade ago the party would not officially call itself Zionist and had avoided joining Zionist institutions.

It’s the same story on the Ashkenazi side. Twenty years ago, Ashkenazi Haredim in Israel refused to acknowledge the ceremonies conducted at military cemeteries on Memorial Day. The military rituals were borrowed from other nations, they complained. Jews must commemorate in their own ancient ways. Then, over the course of the past decade, without fuss or fanfare or explicit acknowledgment of any kind, United Torah Judaism politicians have taken to officiating at those very ceremonies as official representatives of the Israeli government, standing alongside pants-clad female soldiers and laying wreaths at concrete memorials.

Haredi society can change with the times, as long as it does not admit the change aloud.

In 2018, just after he took part in that year’s Lag B’Omer pilgrimage to Meron, Haredi journalist Aryeh Erlich tweeted his concerns about a certain narrow walkway at the site: “The narrow exit path that leads from the bonfire ceremony of the Toldot Aharon [Hasidic sect] creates a human bottleneck and terrible shoving, to the point of an immediate danger of being crushed. And it’s the only exit…. They must not hold the bonfire at that site again before they open a wide and well-marked exit.”

Erlich’s tweet went viral on Friday, exactly three years too late.

In an interview Sunday with the Tel Aviv-area radio station 103 FM about the disaster he predicted so precisely, Erlich rejected any blame directed at Haredi society for the deaths.

“How can you blame the Haredi public?” he demanded. The Meron pilgrimage “is a tradition that’s been going on for 550 years.”

Then who was to blame? “It’s the police that approve the event. There are clear regulations. No event can take place without a safety officer, a policeman who signs off on it and approves it, and that’s what happened at Meron.”

There’s a “sovereign,” he added. That sovereign “decided to ignore [the danger], chose shoddy improvisation instead, and failed to impose safety standards. The Haredi political parties are victims here; it’s not serious for the police to now say that because of [the Haredi parties] they didn’t do what they were supposed to do. The police are supposed to enforce the law.”

It is a pivot in expectations that by its very denial of Haredi culpability signals the shift away from Haredi autonomy. Erlich couches his critique as a defense of Haredi political leaders. But even here, with the blame directed exclusively at the Israel Police, the argument is the same: The police no longer have the right to ignore safety rules merely because Haredi religious sects demand it. How dare the state risk the lives of its Haredi citizens by allowing Haredi autonomy to trump their safety?

The catastrophe at Meron will not lead any in the community to question other elements of its separate existence, such as its independent school system. Nothing so fundamental will change from a single tragedy.

But those now asking the state and the police to take over at Meron, those now questioning, openly and not-so-openly, their leaders’ wisdom and their community’s ethos of separation, will apply that lesson to other things in the future.