Their study, “The ‘Jerusalem Syndrome’ – Fantasy and Reality: A survey of accounts from the 19th century to the end of the second millennium,” published in the Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences (1999), aims to define this phenomenon and looks at nearly two centuries of patterns of tourists who experience a temporary insanity and often assume the role of biblical figures.

|

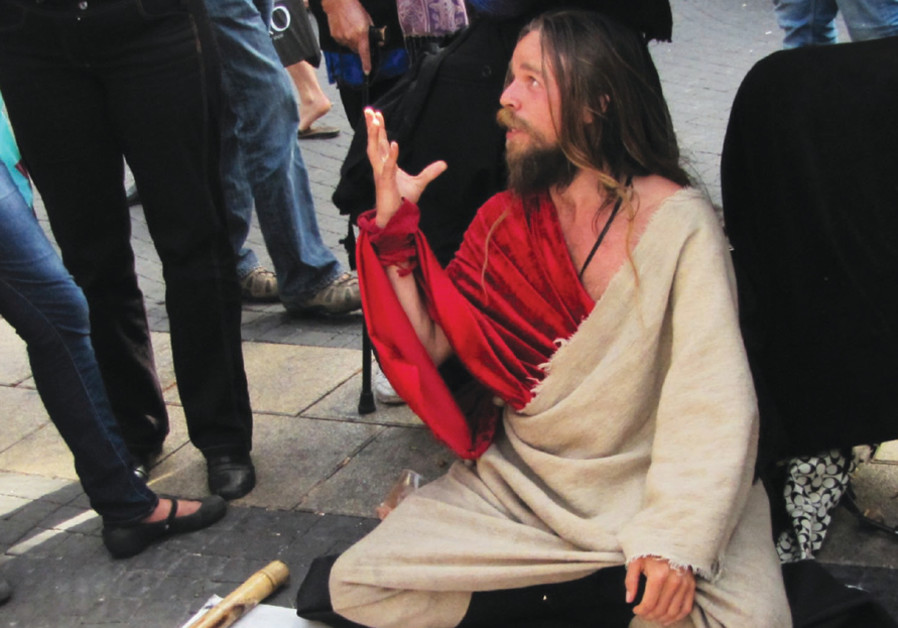

| In Tel Aviv, a man claims to be the Messiah. |

"Jerusalem syndrome” is a diagnosis commonly applied to explain the

behavior of certain unique “characters” who are sometimes seen roaming

the streets of the city.

Donning biblical garb, experiencing delusions or hallucinations, taking on a different name, and refusing to leave the city or Israel itself are some of the symptoms that are considered evidence of this unusual affliction.

Donning biblical garb, experiencing delusions or hallucinations, taking on a different name, and refusing to leave the city or Israel itself are some of the symptoms that are considered evidence of this unusual affliction.

Is Jerusalem to blame for these episodes? Is there even such a

thing as Jerusalem syndrome? What is it about this place that has such a

strong and sometimes dangerous effect on some people?

The phenomenon may have surfaced recently with the disappearance of a British tourist during a visit to Israel several months ago.

Oliver McAfee, 29, disappeared while cycling the Israel Trail in the Negev at the end of 2017.

In January, it was reported that McAfee, still not found, might be suffering from Jerusalem syndrome, as police confirmed that he wrote passages from the New Testament on several pieces of paper and rocks that were found in the desert. The police added to the report that it remained unclear if he had a psychological disorder.

The syndrome is featured in an episode of The Simpsons, aired in 2010, where the Springfieldians make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land with their church group.

While the episode is loaded with fun Israeli-based satire – Sacha Baron Cohen speaking in Hebrew as an almost too accurate stereotypical Israeli tour guide – and a Simpsonified Jerusalem, near the end of the episode Homer has a spat with his devoutly Christian neighbor Ned Flanders, and the scene cuts to Homer riding a camel in the desert. Reaching the Dead Sea after a sandstorm, Homer passes out, face first, in the Dead Sea and awakens to proclaim he is the Messiah, after having a vision of being visited by talking anthropomorphic vegetables.

Homer returns to Jerusalem, donning a toga made of a bedsheet, and makes lofty prophecies. He is diagnosed with Jerusalem syndrome.

Homer ends up on the Temple Mount, standing before Christians, Muslims and Jews and calling for a new religion based on their shared love of chicken, after which all of the assembled stand up and proclaim that they, too, are the Messiah.

Satire often imitates real life, as Homer’s portrayal isn’t too far off from the description compiled by mental health professionals.

JERUSALEM SYNDROME made its first appearance in the medical books in the 1930s thanks to Heinz Herman, who was a Jerusalem-based psychiatrist and one of the founders of modern psychiatric research in Israel.

However, the jury is still out on whether the syndrome arises independently or whether those who are afflicted with it had other preexisting conditions.

Psychiatrists Eliezer Witztum and Moshe Kalian, who for decades have worked extensively with patients suffering with this affliction, have concluded that it’s the latter.

Their study, “The ‘Jerusalem Syndrome’ – Fantasy and Reality: A survey of accounts from the 19th century to the end of the second millennium,” published in the Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences (1999), aims to define this phenomenon and looks at nearly two centuries of patterns of tourists who experience a temporary insanity and often assume the role of prominent biblical figures.

Jerusalem syndrome, according to the study, is a behavioral phenomenon observed in eccentric and psychotic tourists who have been visiting the Holy Land and has been recorded since the beginning of the 19th century. The syndrome “should be regarded as an aggravation of a chronic mental illness, and not as a transient psychotic episode.”

The study notes the spiritual significance of Jerusalem which has been embedded in both Jewish and Christian messianic traditions. The syndrome is related to this notion of Jerusalem being the center of the universe as well as the location of the “end of days” or redemption, depending on whom you ask.

Witztum was a full professor in the division of psychiatry at the Faculty of Health Sciences of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He is the director of the School for Psychotherapy of the Beersheba Mental Health Center. Speaking with In Jerusalem, he explains that nearly all of the cases he has dealt with through the years have proven that a preexisting mental condition is the common thread of all of these cases, and that when a tourist visits Jerusalem, this preexisting condition is triggered in one form or another.

“It’s not a disease but a cultural phenomenon,” says Witztum. “The Judeo-Christian faiths have a lot of messianic prophecies that call on the tourists to have visions, hear voices and go to the Holy Land and do this type of holy work explained in the Bible; but when they get off the plane, it’s another story.”

One of the triggers of the syndrome comes from unrealistic expectations before visiting holy sites.

“When people land here, specifically on religious- based tour groups, they have very high expectations of spiritual significance that were built up prior to the trip; and when they get to these places and their expectations are not met, they become disappointed, and this triggers the symptoms of what is known as Jerusalem syndrome,” Witztum explains.

“Or the expectations are built up so much that, upon reaching such places, especially around the Old City, they become delusional and lose themselves in the moment, triggering a psychotic or schizophrenic episode.”

When this occurs, they most likely end up at Kfar Shaul Mental Health Center, where Witztum has treated dozens of tourists stricken with the syndrome.

“But when these people get to us, nearly all of the patients have preexisting mental conditions on record, and 50% of them are schizophrenic,” he adds.

He related the case of a German chef who walked into a hotel, asked for access to the hotel’s kitchen and spoke with the chef and the kitchen staff.

After a while, he told the staff that he would be taking over the kitchen because he was sent by God to prepare the “Last Supper,” as the end of days was coming.

Naturally, the staff refused and a scuffle ensued, before the police were called.

The German chef was brought to Witztum, who treated him.

Although this phenomenon primarily affects those of the Judeo-Christian faiths when visiting Jerusalem, Witztum notes that similar patterns can be seen among Muslims when they visit Mecca.

“So far, there has been one paper written about this, but I believe this is just a hint of a much larger phenomenon that can be seen in Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia.”

DEBRA NUSSBAUM STEPEN, a Jerusalem-based licensed tour guide and former psychotherapist originally from Los Angeles, has seen this phenomenon in the clinical world and now also in her daily life as a tour guide.

“Walking around the Old City, I have seen people speaking in tongues and having ecstatic experiences in and near holy sites,” Stepen tells IJ. “You are walking in the footsteps of Jesus or King David... and that brings out the connection with the land and the person’s connection with their spiritual side.

“I’ve seen the Christian pilgrim groups and they are experiencing where Jesus walked, and the pastor reads them Scriptures and it just clicks or something.

“You see the Nahman guys singing and dancing – that’s not Jerusalem syndrome; that’s them being them and it’s not crazy. Same thing with newly religious people who dress in all white and dance fervently with their eyes closed on the roof of the Aish HaTorah building [which overlooks the Western Wall].”

She explains that diagnosing Jerusalem syndrome can be a slippery slope: “It is very important not to misdiagnose something that could either be considered psychosis or a spiritual experience.”

Stepen says that people in their late teens and early twenties who are predisposed to schizophrenia and other mental illnesses tend to experience their first episode the first time they leave home.

“I have seen the sudden change and stress of this experience, particularly among gap-year participants, but this is not Jerusalem syndrome and should not be labeled as such.”

“What we are dealing with,” says Witztum, “are mainly the cases that are disturbing the peace: people who sleep on the street or make a scene; but I believe there are more cases that are going unreported.”

The phenomenon may have surfaced recently with the disappearance of a British tourist during a visit to Israel several months ago.

Oliver McAfee, 29, disappeared while cycling the Israel Trail in the Negev at the end of 2017.

In January, it was reported that McAfee, still not found, might be suffering from Jerusalem syndrome, as police confirmed that he wrote passages from the New Testament on several pieces of paper and rocks that were found in the desert. The police added to the report that it remained unclear if he had a psychological disorder.

The syndrome is featured in an episode of The Simpsons, aired in 2010, where the Springfieldians make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land with their church group.

While the episode is loaded with fun Israeli-based satire – Sacha Baron Cohen speaking in Hebrew as an almost too accurate stereotypical Israeli tour guide – and a Simpsonified Jerusalem, near the end of the episode Homer has a spat with his devoutly Christian neighbor Ned Flanders, and the scene cuts to Homer riding a camel in the desert. Reaching the Dead Sea after a sandstorm, Homer passes out, face first, in the Dead Sea and awakens to proclaim he is the Messiah, after having a vision of being visited by talking anthropomorphic vegetables.

Homer returns to Jerusalem, donning a toga made of a bedsheet, and makes lofty prophecies. He is diagnosed with Jerusalem syndrome.

Homer ends up on the Temple Mount, standing before Christians, Muslims and Jews and calling for a new religion based on their shared love of chicken, after which all of the assembled stand up and proclaim that they, too, are the Messiah.

Satire often imitates real life, as Homer’s portrayal isn’t too far off from the description compiled by mental health professionals.

JERUSALEM SYNDROME made its first appearance in the medical books in the 1930s thanks to Heinz Herman, who was a Jerusalem-based psychiatrist and one of the founders of modern psychiatric research in Israel.

However, the jury is still out on whether the syndrome arises independently or whether those who are afflicted with it had other preexisting conditions.

Psychiatrists Eliezer Witztum and Moshe Kalian, who for decades have worked extensively with patients suffering with this affliction, have concluded that it’s the latter.

Their study, “The ‘Jerusalem Syndrome’ – Fantasy and Reality: A survey of accounts from the 19th century to the end of the second millennium,” published in the Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences (1999), aims to define this phenomenon and looks at nearly two centuries of patterns of tourists who experience a temporary insanity and often assume the role of prominent biblical figures.

Jerusalem syndrome, according to the study, is a behavioral phenomenon observed in eccentric and psychotic tourists who have been visiting the Holy Land and has been recorded since the beginning of the 19th century. The syndrome “should be regarded as an aggravation of a chronic mental illness, and not as a transient psychotic episode.”

The study notes the spiritual significance of Jerusalem which has been embedded in both Jewish and Christian messianic traditions. The syndrome is related to this notion of Jerusalem being the center of the universe as well as the location of the “end of days” or redemption, depending on whom you ask.

Witztum was a full professor in the division of psychiatry at the Faculty of Health Sciences of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He is the director of the School for Psychotherapy of the Beersheba Mental Health Center. Speaking with In Jerusalem, he explains that nearly all of the cases he has dealt with through the years have proven that a preexisting mental condition is the common thread of all of these cases, and that when a tourist visits Jerusalem, this preexisting condition is triggered in one form or another.

“It’s not a disease but a cultural phenomenon,” says Witztum. “The Judeo-Christian faiths have a lot of messianic prophecies that call on the tourists to have visions, hear voices and go to the Holy Land and do this type of holy work explained in the Bible; but when they get off the plane, it’s another story.”

One of the triggers of the syndrome comes from unrealistic expectations before visiting holy sites.

“When people land here, specifically on religious- based tour groups, they have very high expectations of spiritual significance that were built up prior to the trip; and when they get to these places and their expectations are not met, they become disappointed, and this triggers the symptoms of what is known as Jerusalem syndrome,” Witztum explains.

“Or the expectations are built up so much that, upon reaching such places, especially around the Old City, they become delusional and lose themselves in the moment, triggering a psychotic or schizophrenic episode.”

When this occurs, they most likely end up at Kfar Shaul Mental Health Center, where Witztum has treated dozens of tourists stricken with the syndrome.

“But when these people get to us, nearly all of the patients have preexisting mental conditions on record, and 50% of them are schizophrenic,” he adds.

He related the case of a German chef who walked into a hotel, asked for access to the hotel’s kitchen and spoke with the chef and the kitchen staff.

After a while, he told the staff that he would be taking over the kitchen because he was sent by God to prepare the “Last Supper,” as the end of days was coming.

Naturally, the staff refused and a scuffle ensued, before the police were called.

The German chef was brought to Witztum, who treated him.

Although this phenomenon primarily affects those of the Judeo-Christian faiths when visiting Jerusalem, Witztum notes that similar patterns can be seen among Muslims when they visit Mecca.

“So far, there has been one paper written about this, but I believe this is just a hint of a much larger phenomenon that can be seen in Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia.”

DEBRA NUSSBAUM STEPEN, a Jerusalem-based licensed tour guide and former psychotherapist originally from Los Angeles, has seen this phenomenon in the clinical world and now also in her daily life as a tour guide.

“Walking around the Old City, I have seen people speaking in tongues and having ecstatic experiences in and near holy sites,” Stepen tells IJ. “You are walking in the footsteps of Jesus or King David... and that brings out the connection with the land and the person’s connection with their spiritual side.

“I’ve seen the Christian pilgrim groups and they are experiencing where Jesus walked, and the pastor reads them Scriptures and it just clicks or something.

“You see the Nahman guys singing and dancing – that’s not Jerusalem syndrome; that’s them being them and it’s not crazy. Same thing with newly religious people who dress in all white and dance fervently with their eyes closed on the roof of the Aish HaTorah building [which overlooks the Western Wall].”

She explains that diagnosing Jerusalem syndrome can be a slippery slope: “It is very important not to misdiagnose something that could either be considered psychosis or a spiritual experience.”

Stepen says that people in their late teens and early twenties who are predisposed to schizophrenia and other mental illnesses tend to experience their first episode the first time they leave home.

“I have seen the sudden change and stress of this experience, particularly among gap-year participants, but this is not Jerusalem syndrome and should not be labeled as such.”

“What we are dealing with,” says Witztum, “are mainly the cases that are disturbing the peace: people who sleep on the street or make a scene; but I believe there are more cases that are going unreported.”

No comments:

Post a Comment