The Jewish word that no one uses anymore ...

(I'll Add One - (Shanda Far Der Yidden!)

A word that comes straight out of the Jewish moral vocabulary list. Sometimes, it is about our own families.

(RNS) — There is a Yiddish word that our grandparents used that has fallen out of use.

The word is shanda — shame.

Some would say: Good riddance.

For several generations, the idea and living reality of shanda served as fuel in our personal and communal Jewish engines.

Consider the way that we used that word.

If something was a shanda fur die goyim — what did that mean?

It meant that whatever it was — it was something that would bring shame, disrepute or embarrassment to the Jews — and it was something that we should not let the gentiles see.

Why?

Because we feared antisemitism. Shanda was our internalized sense of powerlessness.

We screamed shanda about any number of people:

- Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, the atomic bomb spies.

- Their nemesis, the attorney Roy Cohn (who my parents believed was a life form somewhat lower than algae).

- The disgraced arbitrager and inside trader, Ivan Boesky, who so greatly understood that he was a shanda that he asked that the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York remove his name from their library.

- Bernie Madoff, of the Ponzi scheme — a man who targeted his fellow Jews and Jewish organizations, and whose criminality left serious and enduring wreckage in its wake.

- And, most recently, the wealthy sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein.

These were all Jews who brought disrepute to the Jewish people. Hence, shanda!

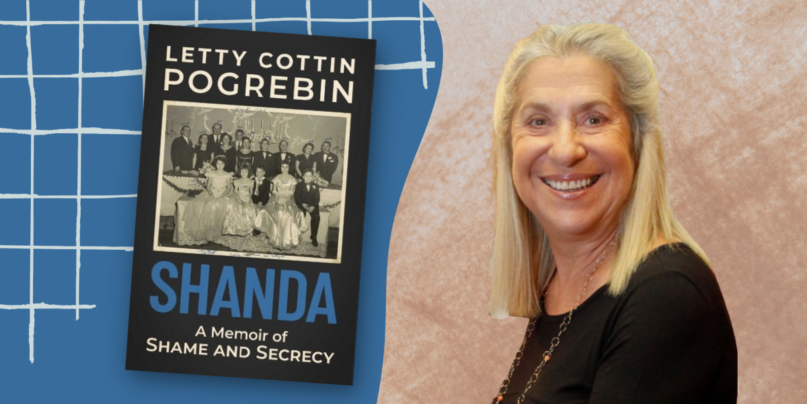

A new book by Letty Cottin Pogrebin, the feminist author and activist (co-founder of Ms. magazine) takes the idea of shanda to a new, deeper level. The book is, appropriately, “Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy.”

The best term I can invent for what Letty does is “family archaeology.” She digs into her family stories, generation by generation, level by level. She discerns the layers of fables and outright fictions that undergird her narrative — all as a way of getting real, getting clear and getting whole.

She writes: “Every family has its underbelly. Mine was fat with pretense, the denied, the obscured, the unsaid.” Hiding is my heritage, she says.

There is something very Jewish about hiding and secrecy. Over the years, I have ruminated on the essential Jewish nature of the superhero with a secret identity — superheroes invented by Depression-era Jews who wanted to assimilate, who understood secrecy and hidden identities.

Letty reminds us that biblical figures often disguised themselves. The entire Book of Genesis is one long masquerade party — for example, Jacob disguises himself as Esau, Tamar disguises herself as a prostitute, and Joseph disguises himself as an Egyptian overlord. On the holiday of Purim, masks have a starring role.

Letty embarks on a journey into her family’s past, which includes her own past.

Among the things she unearths and confesses:

- Her own abortion.

- Her encounter with a drunken Irish author that almost ended up in rape.

- A divorce from two generations ago.

- Her own bout with cancer. (How did our parents speak of that illness? In hushed tones that you would normally reserve for a public library or a synagogue. The “C-word.” “The big C.”)

- A cousin who is gay.

- A child who died in infancy.

- Her parents’ previous marriages.

- Mothers who died in childbirth.

- Siblings who showed up unexpectedly, whom she never knew she had.

- Unhappy marriages.

In particular, and most poignantly, there are the stories about Letty’s father, Jack Cottin. He was a communal leader, apparently successful, dashingly handsome.

But, it turns out that Jack Cottin was hiding something. Beneath the façade, under the masks, he was a financial failure. All of his outward success turned out to be mere posturing, a mirage.

Was it possible that my father’s unilateral decision to sell our house and relegate me to a daybed in his new apartment’s entry hall was not born of selfishness and insensitivity to my feelings of loss and abandonment, but of shame and his refusal to admit that he was unable to afford an apartment with a second bedroom?

Could it be that the reason he didn’t give me any spending money in college was not to teach me financial independence but because he didn’t have a dollar to spare? What a great relief it would be, even these many years later, were I able to believe that his actions sprang from a paucity of resources, not of love. Was he performing prosperity to save face? If so, I would sympathize with him retroactively and forgive him posthumously.

Few things could shame a husband or father more than being unmasked as an inadequate provider. I knew that. But I never imagined my self-assured dad would wear any kind of mask in the first place. Looking back, I recognize now that compelling social forces in his upwardly mobile Jewish community — namely masculine pride and the loom of the shanda — were enough to make my father, or any man of his generation, lie about his finances.

As Letty put it, knowingly: “In the Jewish world of the 1950s, a man who couldn’t support his family was not a man.”

What gets me about this wonderful, lyrically written book is that it proves something we all know: The more personal a story, the more universal it is. Every reader will find themselves in these pages. These are all of our stories.

But, this leaves me with a question about the future of Jewish identity.

Once upon a time, our parents and grandparents could, and would, complete the following sentence: “Jews don’t (fill in the blank).”

We had our list of answers:

- “Jews don’t buy retail.”

- “Jews don’t make racist jokes.”

- “Jews don’t play or enjoy violent sports.”

- “Jews don’t hunt.” (Because of the prohibition against cruelty to animals, and also because the biblical Esau was a hunter — which was, by the way, a shanda).

I once gave a sermon on that last statement — “Jews don’t hunt” — in a Southern congregation.

During the oneg Shabbat, a few congregants approached me to tell me, in no uncertain terms, that Jews do, in fact, hunt.

Is it still possible to make the statement: “Jews don’t … “?

I wonder.

And, I wonder what happens to a culture when there are no longer taboos.

I believe the era of shanda has vanished — if only because our children and grandchildren will lack the ethnic Velcro to see Jewish bad actors as somehow inextricably linked to them.

While shanda has evaporated, another Yiddish word might be experiencing a renaissance — though perhaps not in the original Yiddish.

I am talking about past nischt — that there are things Jews should not do.

Shanda was about what others might think. The Other has the power to define you and evaluate you.

Past nischt is about what we — in the form of Jewish history, Jewish values, and we might even dare to say, God — might think. We, or our surrogates, have the power.

I feel that sense of past nischt all over the place, and I suspect Letty would agree with me.

In particular, I feel that sense of past nischt not only in an ethical sense, but increasingly in the sense of what is going on in our world today.

I know Letty knows this, because of her leftward leanings on Israel. She might think Benjamin Netanyahu was a shanda, but a more concise critic of Israeli policies might hope a people that has been powerless would say, about the gratuitous use of power: Past nischt.

Sometimes, I agree with her.

I will go beyond that.

When I encounter Jews who behave badly, it is not only a case of shanda; it is a case of past nischt.

As in: They should know better and be better and act better.

As in: A people that has a covenant with God should know better, be better and act better.

In the words of my friend, colleague and teacher, Rabbi Lauren Berkun of the Shalom Hartman Institute, in her interpretation of the teachings of Rabbi Donniel Hartman (whose father, the late Rabbi David Hartman, Letty cites in this book):

We answer to a higher authority, we answer to a higher standard, and that is the standard that’s worthy of who we perceive we ought to be. A standard that embraces exceptionalism, not in any sense of arrogance, but in the sense that “you shall be unto me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.” This is what you must work to become. If we fail to do so, we are failing to live up to our mission as a nation charged to be God’s covenantal partners and consequently to be a light that sanctifies God’s name and enables God to be the God of the world.

If we fail in doing that — well, that would be a shanda.

I love this book, and I suspect I will be returning to it frequently.

You will love it as well — probably because you will see yourself, and your family, and your own complicated narrative in its pages.

With that, may we all live in such a way that our names appear in the Book of Life.

https://religionnews.com/2022/09/28/shanda-letty-cottin-pogrebin/

6 comments:

Strangely, growing up in London UK, and immersed in London-Jewish (East End) talk, I never heard the word ‘’Shanda’ until I met American Jews. Conversely, the word ‘Lobbes’ (=mischievous little brat) seems to be unknown outside England.

@anon 3:25PM

Not so. Living in the USA, my father, a Holocaust survivor, at times called me a “lobus” with the same meaning as you describe. The word comes from Lobo, a wolf. derived from the Latin Lupus.

Dear letty, thanks for this beautiful book. I cried for 3 hours straight reading it. It reminded me the many times mom would tell me It's a shanda the way I dress, when in truth it was a new years resolution to never wear new clothing, to just do my part in saving the environment. But what do you want from mom, It's a real shanda that it past niSht to read this book.

Uriah’s wife: I suspect your dad came from Poland. Some years ago there was a correspondence in the UK Jewish Chronicle about the etymology of the word. Conclusively, it is from the Polish word for “scallywag”.

Also - found this on the web — the author seems to be unaware of the earlier (early 1990’s?) correspondence in he same newspaper! https://www.thejc.com/judaism/jewish-words/lobbes-1.8024

Thanks, was never able to figure out how to say scalywag in Yiddish

Post a Comment