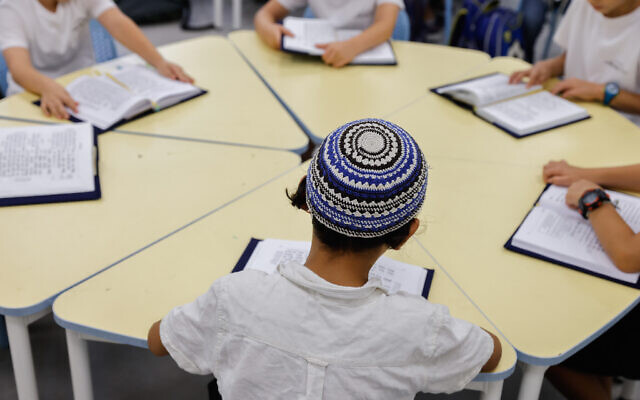

Religious students report sexual abuse at twice rate of secular school peers – study

Report by liberal Orthodox group, based on Welfare Ministry data, finds those who attend state-religious and Haredi schools are much more likely to experience sexual assault

Students who attend religious schools are more than twice as likely to have reported being sexually abused than those in secular public schools, according to a dramatic report from a liberal Orthodox organization released Sunday, based on Welfare Ministry data.

Out of every 1,000 students in the secular state school system, 1.04 were receiving treatment of some kind from the Welfare Ministry after having been sexually abused. In the ultra-Orthodox system, that number was nearly double — 1.98 — and in the state-run religious school system it was more than twice as high at 2.39, according to the study by the Ne’emanei Torah Va’Avodah Movement, a progressive religious rights group.

Shmuel Shattach, the head of Ne’emanei Torah Va’Avodah, said the study showed that separating classes by gender, as is done in ultra-Orthodox schools and many state religious schools, does not necessarily make any difference in cutting down on sexual abuse of children.

“People say, let’s gender-separate schools and we’ll be safer. In mixed schools, there’s definitely abuse. That’s something that people would always tell me. So we checked it,” he said.

The figures used in the report were gleaned from the Central Bureau of Statistics, which gathered them from reports from municipal social services offices that were collected by the Welfare Ministry. The figures only noted what type of school the victims attended, meaning the abuse did not necessarily occur within the schools.

These figures only comprise reported cases of sexual abuse. Unreported cases are not included nor are they estimated. According to Shattach, the actual numbers are likely even higher as Israel’s religious community typically underreports abuse cases.

“None of the experts we consulted with for this study were surprised by the results. None of them said, ‘No, your numbers must be wrong.’ Every professional who deals with this issue said that the figures we found generally reflected reality,” Shattach said.

The study found that abuse rates were higher among both male and female students in state-religious and in ultra-Orthodox, or Haredi, schools. However, male students in those religious frameworks experienced far higher rates of abuse — more than three times higher — than their secular counterparts. According to the figures, 0.61 male students in secular schools out of every 1,000 were being treated after having been sexually abused, while in Haredi schools it was 2.07 and in national-religious schools it was 2.3.

The data did not break down abuse rates by individual school but rather according to school type, which limited Shattach’s ability to draw wider conclusions about abuse rates of coed schools compared to gender-segregated schools, since not all religious schools separate by gender.

“I can’t prove definitively that mixed settings are better, but I can absolutely prove that gender segregation doesn’t help,” he said.

Shattach — who drew a clear distinction between the findings, based on unequivocal data, and his analysis of it, which reflects his and his organization’s views — offered a number of explanations for why there might be higher rates of abuse among students who attend religious schools.

He noted that gender-separated state religious schools have a higher number of male teachers, who are statistically more likely to commit sexual abuse than female teachers.

The teachers in state religious schools are also typically not as well trained or supervised as in secular schools, according to multiple state comptroller reports.

Many of the towns with the highest rates of reported sexual abuse were West Bank settlements, which generally lack the same level of government oversight as municipalities in Israel proper.

Shattach, who advocates for coed schools, said gender-segregated schools also instill a false sense of security among parents and typically do not have strong sex education programs, though he said they had made notable and laudable improvements on the latter front.

“In a mixed society, we don’t have a false sense of security. We are constantly on top of our kids. ‘Where are you going? Who are you with? Who are your friends?’ We also talk about [sexual abuse], there are conversations about it. What constitutes abuse? Kids have the terminology to understand the issue, to understand what’s right and what’s wrong,” Shattach said.

“In gender-segregated societies, there’s that false sense of security. Parents think, ‘OK, it’s just boys,'” he said. “There’s generally less attention paid to it. So the kids don’t have that terminology. A boy who grew up in that educational system, even if he were to see something happen, he wouldn’t be able to connect it to anything.”

He said his organization’s support for coed study partially stemmed from a desire to force adults to teach children about the complexities of the world.

If you place children in a bubble “they don’t have that exposure,” he said.

Shattach surmised that family structures among the religious, who tend to have more children than their secular counterparts, could also be a contributing factor to the higher rates of abuse.

“When you have large families, practically it’s more difficult to have control over what goes on,” he said. “When you have three kids, you can track where they all are. When you have 10, it’s more difficult.”

1 comment:

So, what actions will the ultra-orthodox take to address the abuse issue?

Post a Comment